Man, this last couple of weeks has seen a veritable tsunami of sexual-harassment allegations, right? And while some of the accused are silent or flat-out denying any culpability, others have been swift to apologise.

Photo: evil nick

But most of these apologies have been anything but sincerely contrite. Take, for example, President George H.W. Bush’s apology for having groped young women: “To try to put people at ease, the president routinely tells the same joke – and on occasion, he has patted women’s rears in what he intended to be a good-natured manner. Some have seen it as innocent; others clearly view it as inappropriate. To anyone he has offended, President Bush apologizes most sincerely.”

This is the classic “I’m sorry you’re upset” apology, which has to rank up there with one of the more enraging things one person can say to another. It accepts no responsibility for harming the other person and only commiserates with their distress, like, “Wow, I’m so sorry you’re sad about your cat’s death,” not, “I’m sorry I killed your cat.” It very subtly implies that there’s something wrong with your emotional makeup that you’re so upset about something that is, evidently, not even worth apologising for.

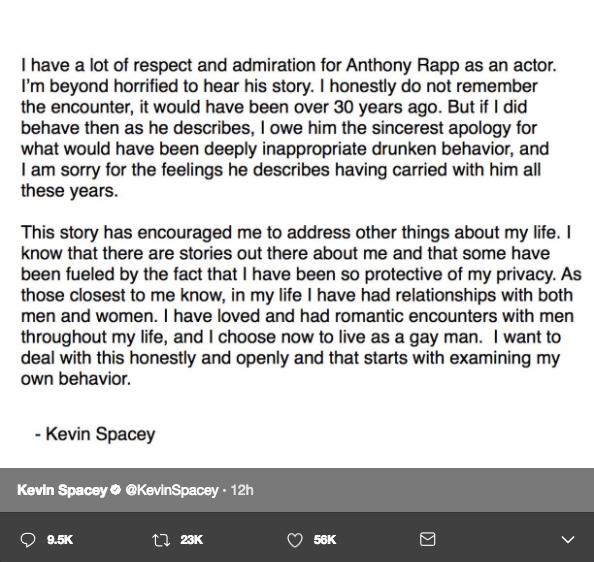

Or take, for example, Kevin Spacey’s response to the allegation by Anthony Rapp that Spacey sexually assaulted Rapp when he was 14 and Spacey was 26:

In this one, Spacey says he doesn’t remember (casting doubt on the allegation), he was drunk (like being drunk excuses reprehensible behaviour), and finally – this is the doozy – uses his apology to come out to the world. Talk about deflection and misdirection. Talk about not apologising for assaulting a child.

Or consider Harvey Weinstein’s statement, in which he said, “I came of age in the ’60s and ’70s when all the rules about behaviour and workplaces were different. That was the culture then,” which prompted its own wave of mockery on Twitter:

https://twitter.com/andizeisler/status/916017128074969089

Guys, how hard is it to sincerely apologise? Now I understand that one’s attorney might advise one to not say sorry because it can be construed as admitting wrongdoing. In that case, don’t say anything at all – this mealy-mouthed nonsense only makes you look like a mealy-mouthed jerk.

[referenced url=”https://www.lifehacker.com.au/2017/10/how-to-tell-if-youre-mansplaining/” thumb=”https://i.kinja-img.com/gawker-media/image/upload/t_ku-large/gebltuzqojwsv2wjhuqs.jpg” title=”How To Tell If You’re Mansplaining” excerpt=”Mansplaining has become one of the defining phenomena of the 21st century, and its pedantic tentacles touch everything from the last US presidential campaign to online riffs about how women just can’t ‘get’ Rick and Morty. While we’ve come a long way towards naming and shaming the mansplainers in our midst, on the flip side of that exchange, catching yourself in the act (and taking a step back) can be a challenge for anyone who’s spent their whole life assuming that they always have something interesting and useful to say, despite all evidence to the contrary.”]

So what does make a good apology? Psychologist Karina Schumann published a paper on 1) why it’s so hard to effectively apologise and 2) the eight components that constitute a sincere apology. Number one is “You actually have to use the words I’m sorry”, and number two is “Acknowledge that you messed up”. Toss in there “Tell the person how you’ll fix the situation” and “promise to behave better next time”, and you’re on your way to making amends.

Don’t do what Robert Scoble did, which was emphatically not apologise and in fact litigate, in a blog post, every accusation against him. Against legal advice. And in his second sentence he takes a page from George H.W. Bush’s book: “I am sorry that so many women feel wronged by me.” And don’t do what venture capitalists Justin Caldbeck and Dave McClure did after being forced out of their jobs, which is post jokey new job titles on their LinkedIn profiles. Don’t care if anyone thinks you’re contrite? At the very least keep your mouth shut.

Comments