One hundred fifty years ago, the Great French Wine Blight nearly wiped out an industry that today produces some 40 billion bottles of wine a year. The only solution was a radical fusion of species that remains essential to the success of the wine market. Here’s the story of how humanity hacked the wine grape.

Photo Credit: Graham via flickr [CC BY 2.0]

European Colonization And Transoceanic Wine Grapes

When the Romans expanded their empire to Paris, they brought their wine with them. The earliest European colonists did the same in the Americas, where they attempted to grow their prized grape vines. Vitis vinifera, the European species of wine grape responsible for familiar wines like Chardonnay and Pinot Noir, was first planted in North America by French settlers in the 1600s. (Correction: Vitis vinifera first reached North America via Spanish settlers in the 1500s, but was only introduced to the present-day U.S. by the French in the 1600s.)

Most of these alien grapes succumbed to local pests and pathogens. But the settlers were undeterred. They began experimenting with local grape species, such as Vitis riparia and rotundifolia. These plants thrived in their native soil, but the wine they produced could not compare to the great wines of Europe.

To produce an acceptable wine, early American vintners had to get creative. By grafting vinifera vines to the roots (aka “rootstocks”) of American vines, grape growers could preserve the genetics of the vinifera grapes (ensuring a good-quality wine), while protecting them from unknown disease agents in the soil with local roots.

[Above: A grafted vine with the fruit-bearing species (scion; darker wood) above the graft union, and the rootstock species below. Riccardo Pastore, CC BY 2.0.]

In the 18th Century, the wine industries of both Europe and North America flourished, and vintners began importing American vines into France, the epicentre of viticulture. Competition for growing the best new wine grapes grew.

The advent of steam power significantly cut the transit time across the Atlantic in the 19th Century, fuelling the rapid establishment of experimental vineyards full of both American and hybrid vines all across France. At the time, nobody gave much thought to the possibility of plant diseases being transmitted through this unregulated trade.

Amidst all the excitement surrounding the growing wine economy, the vine importers failed to notice a stowaway on their cargo. This oversight set off a biological chain reaction that would forever change how grapes would be grown around the world.

The Great French Wine Blight Begins

In the mid-1860s, vintners in France began noticing that some of their vines were suffering from an ‘unknown disease‘ that would progressively kill the plants. A vine or two in the middle of a vineyard would yellow, droop, and die. The next year, its neighbouring vines would begin to show signs of illness. Within two years, the diseased vines could be found rotting from fruit to root. Over just a few seasons, entire vineyards collapsed, leaving more than a few French families scrambling to make ends meet. The blight had begun.

In 1868, at the behest of the local government, a French pharmacist named Jules-Émile Planchon joined a commission of politicians and winegrowers to investigate what appeared to be a looming national disaster. Planchon, along with various committee members, visited a sick vineyard in southern France, near Montpelier. The team initially dug up several sickly vines, but, apart from their apparent disease, nothing about them looked amiss. By chance, a healthy vine was then uprooted and inspected, revealing a grotesque spectacle, as described by Planchon:

“Loupes were trained with care upon the roots of uprooted vines: but there was no rot, no trace of cryptogams; but suddenly under the magnifying lens of the instrument appeared an insect, a plant louse of yellowish colour, tight on the wood, sucking the sap. One looked more attentively; it is not one, it is not ten, but hundreds, thousands of the lice that one perceived, all in various stages of development. They are everywhere . . .”

Phylloxera feeding on grape vine roots. Joachim Schmid, CC BY 3.0 DE.

Though the potential culprit had been found, the team — untrained as it was in the insect sciences — had some lingering questions. Why were these bugs living on healthy roots but not dead, decaying ones? Moreover, were these little bugs in fact causing this disease — or was their presence merely a side-effect?

Unable to conclusively address these issues, Planchon and his colleagues soon found themselves targeted by the wine establishment of northern France. Not only was snobbery at play (southern France had a reputation for producing inferior wine), but French scientists had recently settled on what was called the physiological, as opposed to ontological, model of disease. In this model, disease was presumed to be caused by an inherent, physiological flaw in an organism, rather than any external factor. This model implied that the lice were not causative agents, but freeloaders benefitting from the inherently diseased grape vines.

Some alternative explanations for the blight included meteorological conditions, weaknesses within the vines, or even ostensibly “general circumstances,” as opposed to the teeming bugs that were found on the roots of healthy vines in every newly-afflicted vineyard. The debate raged on, as these bugs wreaked havoc on an ever-increasing proportion of the wine country of Western Europe.

Luckily, Planchon refused to back down. He published his descriptions of the insects, suspecting that they might be related to an American species called phylloxera. To silence his critics, however, he needed confirmation.

An American Entomologist Helps Connect The Dots

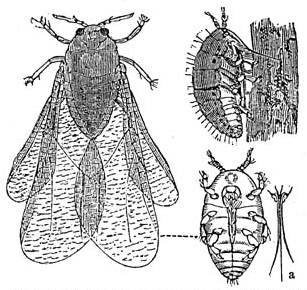

Phylloxera (Daktulosphaira vitifoliae). Public domain/Wikimedia Commons.

In 1870, C.V. Riley, an esteemed entomologist from Missouri, read Planchon’s descriptions and realised that these insects were, in fact, American phylloxera. But the phylloxera Riley knew preferred to live on the leaves of American grape vines. Planchon’s suspects had been found only on European vinifera — and they had been found on the plants’ roots.

Planchon would eventually connect his observations with Riley’s when it was discovered that, in France, the phylloxera preferred the leaves of imported American vines, and the roots of local French vines.

The insects were the same, even if their predilections differed between species of vine. And the absence of phylloxera on dead roots could be explained by the insects’ feeding strategies. Phylloxera used a long mouth appendage to suck sap from vine roots, exposing the roots to a toxin that would prevent the roots’ wounds from healing, eventually killing them. By the time the roots were dead, phylloxera had moved on to healthier roots. And the insects left no calling card.

The science was stacking up in favour of phylloxera being the cause of the blight. Meanwhile, inadequate strategies were being devised to address the blight. Some vintners discovered that flooding their vineyards could rid their vines of phylloxera, albeit at a high and unsustainable cost; others managed to set up vineyards on Mediterranean beaches, but the resulting wines were bland, and entire vineyards washed away during unusually high tides.

By 1874, experts had finally come to a grudging consensus that phylloxera was the cause of the wine blight. But if American bugs were destroying French vines, then the French decided they would defend their local vines at all costs.

La DéfenseFalls to La Réconstitution, and a New Era of Viticulture Commences

To avoid acquiescing to an American solution to an American problem (that is, growing American vines instead of vulnerable French vines), the French began their recovery by incentivizing the invention of a chemical remedy for phylloxera: la défense. The government offered 300,000 francs to the inventor of an insecticide that could save the French wine industry, and received over 600 suggestions between 1874 and 1877, including remedies like goat and human urine.

A toxic chemical, carbon disulfide, was also tested, even though it sometimes killed vines in addition to phylloxera. One rail company went so far as to subsidise shipping of this chemical to compensate for shipping revenue lost due to the wine shortage itself. Sometimes, communities of vintners would vote on whether to use carbon disulfide in an entire district, forcing even the vineyards of dissenters to be doused with the substance.

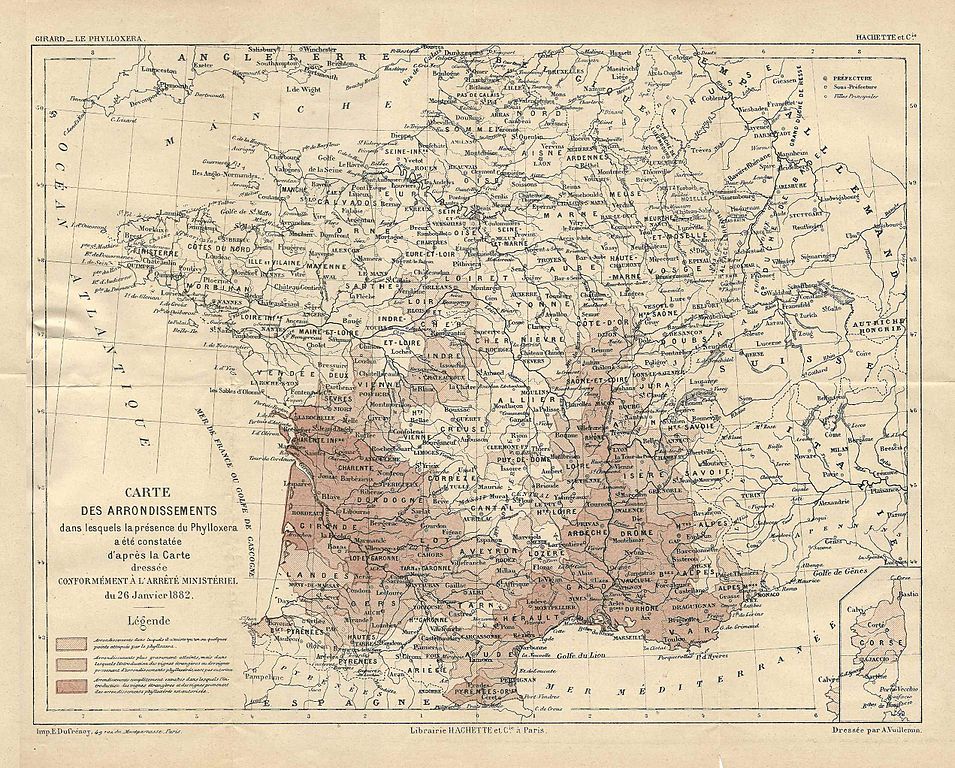

An 1882 map of the spread of phylloxera throughout France. Maurice Girard, Public Domain.

Many wine makers opposed these heavy-handed use of insecticides. As insecticide application continued to fail, French vintners began to surreptitiously plant phylloxera-resistant American grape vines, at first just to produce any booze to take the edge off of their ongoing plight.

By the early 1890s, the French wine industry had relented with la défense, and began the slow process of la réconstitution: developing hybrid or grafted vines that could thrive in French soils; resist phylloxera; and still make great wine.

This was easier said than done. Some experts believed that American rootstocks could be the basis for successfully grafting vinifera in Europe, while others were more smitten by the prospect of breeding hybrid strains. A fuzzy, 19th Century understanding of genetic heritability didn’t help either camp, because scientists couldn’t agree on the details of how traits — like resistance or eventual wine quality — would be mixed during vine breeding versus grafting.

Even Planchon, the keen detective who revealed phylloxera as a destroyer of grape vines, stumbled in his first attempts to save the wine industry with grafting. Over 700,000 French vine cuttings, grafted onto American rootstocks, had died between 1872 and 1873, after being planted according to Planchon’s early advice.

Eventually, methodical experimentation in southern France produced both types of genetic cures for phylloxera. Hybrids and grafted vines soon achieved a true la réconstitution, and the rest is history; and France’s early experience with phylloxera provided many of the solutions that would later be used in other wine-making countries.

A Changed World

France, though central to the story of phylloxera and the upending of traditional viticulture, was not the sole victim to the wine blight. Phylloxera was found in vineyards near the city of Sonoma, California in 1874. American vintners, just like the French, dithered in a state of denial for decades, resulting in phylloxera’s spread throughout the state by 1900. Eventually, California’s wine industry adopted the well-honed tactics of the French to stave off the bugs, often using vinifera grafts on top of American rootstocks.

Phylloxera also ravaged vineyards across Europe, as either American vines, or newly-infected French vines, travelled east and south, as far as Croatia and Greece. Australia and New Zealand were eventually affected, too, though Western Australia and Tasmania remain phylloxera free (partially due to restrictions on the trade of grape vines). Chile remains the sole major wine producer that has completely evaded phylloxera, perhaps because it is surrounded by mountains.

A vineyard in Chile – free of phylloxera, vines growing on original roots. Mariano Mantel, CC BY-NC 2.0.

Hybrid vines eventually became relegated to the production of cheap wines outside of Europe, especially after France’s ban on hybrid vines was adopted in 1979 by the European Union. Note that this ban does not apply to American rootstocks; nearly all French wine, including expensive French wine, comes from vines grafted onto American roots.

Interestingly, a few, rare French vineyards somehow escaped phylloxera’s wrath, and wine from these vineyards is highly prized. The biological basis for their evasion is a complete mystery, however; as the owner of one of these vineyards explained to The New York Times in 2006, “we have no scientific reason that I know for why we don’t have phylloxera. We might not be able to produce a single bottle next year.”

This admission reveals a sobering truth about phylloxera: While we have kept it at bay for about a century, we have never eradicated it, nor do we understand exactly why some rootstocks provide resistance. So what does the future hold for a wine industry that has struck a tenuous truce with these little devils?

The Fight For Our Wine Is Not Over

California vintners got to experience the consequences of this seeming stalemate with phylloxera just 35 years ago, when California vineyards underwent another near-catastrophe that eerily resembled the Great French Wine Blight. It began with just a few dying vines. These vines multiplied. Eventually, the unlucky vintner affected by the mysterious die-off called in some local vine experts.

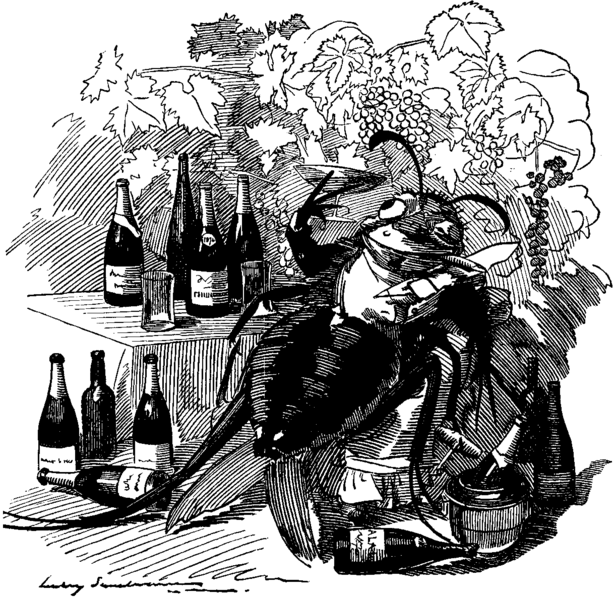

When University of California, Davis professor Austin Goheen dug up a vine at the disease-stricken vineyard in 1982, it bore the classic signs of phylloxera infestation. But all grape vines in California were being grown on presumably phylloxera-resistant rootstocks, developed a century earlier to prevent just this sort of problem. [Pictured at left: “THE PHYLLOXERA, A TRUE GOURMET, FINDS OUT THE BEST VINEYARDS AND ATTACHES ITSELF TO THE BEST WINES.” Punch, September 1890, Edward Sambourne, public domain.]

It took modern scientists at UC Davis seven years before they determined that an evolved “biotype” of phylloxera had overcome the resistance of AxR #1, the particular rootstock that was prevalent in California. And in fact, this American rootstock had been rejected by the French during la réconstitution for its mediocre phylloxera resistance, but was nevertheless used by California growers for their vine grafts for decades.

By the time the new phylloxera’s ruse was up, it had spread across California, decimating vineyards and requiring their reconstitution on newer phylloxera-resistant rootstocks. Every vineyard had to replace every single one of its rootstocks. The cost to California’s economy? About $US1 ($1) billion.

The fight to keep the wine flowing will likely never end. Just this past October, a fungal disease called esca was reported to threaten the French wine industry once again. Wherever we propagate anything in large numbers, nature will eventually catch up to us, and agriculture will be forced to adapt.

I caught up via email with Dr. Andy Walker, UC Davis professor of viticulture and enology, whose lab remains on the front lines of the battle to keep viticulture viable. The Walker Lab continues to develop even newer pest-resistant rootstocks, while also studying the genetics that underlie both vine and pest evolution.

Though modern chemistry and genetics have given agriculture plenty of new tools to fight pests, the ancient practice of grafting, honed during the Great French Wine Blight, remains the method of choice for protecting grape vines. “Rootstocks are the ‘cure-all’ for many soil-borne pests and diseases, but not all,” Walker says. “In the past fumigation and pesticides controlled some of these issues, but if phylloxera are present, rootstocks are essential.”

Walker’s lab also uses genetic engineering to test out the function of individual genes in grape vines, but Walker says genetic modification can’t easily replicate the complex ways in which resistant rootstocks actually ward off pests and disease. Regardless, though, vintners will be forced to tinker with vine biology for years to come, splicing the vines of one species onto the roots of another, hopefully one step ahead of any impending threat.

It’s hard to compare modern wine, which is all grown on grafted vines, to pre-phylloxera wines (the notable exceptions being Chilean wine, and wine from the occasional European vineyard that was spared from the blight). But Walker says it is unlikely that grafting would alter many of the qualities of wine made from the original, fruiting vines.

In any case, high-end wine connoisseurs will have little say in whether vintners adopt new techniques for keeping their trade afloat, if they want to continue drinking wine at all. “I think climate change, and increased concerns about fungicide use, will force an acceptance of new varieties,” Walker says.

Sources:

Saving the vine from Phylloxera: a never-ending battle (George Gale); Wine Blight: How the French Wine Industry was Nearly Wiped Out (Vanessa France); The Great French Wine Blight (Pat Montague); The Great Escape (Kerin O’Keefe).

Comments