You can be forgiven for not understanding human behaviour very well. People are complicated, and it’s hard to understand why we do what we do, especially since the answer is likely due to a trick our minds are playing on us. Simply eliminating the variables necessary to test a hypotheses about the cause of even the most basic things we do is all but impossible. So don’t be too mad at yourself if you accepted one of these 12 commonly held beliefs about how our minds and personalities work; a lot of other people did too (and we likely won’t ever know why.)

The ‘alpha’ and ‘beta’ theory

This idea that some people are inherently “alpha,” (naturally suited to the leadership role in a hierarchy) and some are “beta” (followers) is based on observations of hierarchies within the animal kingdom. These observations have not only been misunderstood in nature, they’ve been widely applied to human society is a way that is anything but scientific.

Things are way more complex than “alpha vs. beta” among animals. The term isn’t even used any more in the study of wolves, as research reveals that “alpha males” are actually fathers, as opposed to the most badass wolves. Same with the “pecking order” in groups of roosters and hens. Among chimpanzees, group leaders often are physically strongest, but they also tend to be generous, empathetic, and foster group cohesion — the opposite of the “bully” stereotype often associated with human “alpha males.”

Humans lead considerably more nuanced lives than animals. We are required to adopt different roles in different situations — someone might be the alpha at the chess club meeting, but a beta during a dodgeball game, for instance. The alpha theory just isn’t a useful or accurate way of categorising people.

Smiling will make you happier

The idea that if you force yourself to smile, you will feel happier is part of “the facial feedback hypothesis,” which suggests that our experience of emotions is influenced by feedback from our facial expressions. The idea has been around for a long time — Charles Darwin was a proponent — but the most well known recent study of fake-smiling was done in 1988 by social psychologist Fritz Strack. He had subjects hold a pen in their mouths to force them to “smile” then showed them some comics. According to his research, smilers said they found the comics funnier than the control group. But in 2016, 17 labs tried and failed to replicated Strack’s results. Maybe things have changed since then. Or maybe the original result was an outlier.

Not that facial feedback is entirely bunk; it just doesn’t seem to make much of a difference. A meta-analysis of facial feedback research concludes, “the available evidence supports the facial feedback hypothesis’ central claim that facial feedback influences emotional experience, although these effects tend to be small and heterogeneous.”

The “marshmallow test” and delayed gratification

Back in 1967, psychologist Walter Mischel started testing preschoolers by putting a marshmallow in front of them and telling them, “you can eat this now, or I’ll give you two marshmallows when I return.” Some kids ate the marshmallow right away; some toughed it out until the second treat was delivered. Follow-up research seemed to show the kids who were able to delay gratification led generally more successful lives through their 20s and 30s.

The experiment was flawed for a number of reasons. The test group was small (only 90 kids) and they were all children of faculty and staff at Stanford — not exactly a representative sample. The experiment didn’t even control for whether the kids liked marshmallows. A similar study in 2018 with a larger sample size didn’t find the same correlation as the original experiment. Instead, it found a weak connection between early age self-denial and later success that disappeared entirely when socioeconomic factors were controlled for. Apparently, rich kids are better at not eating marshmallows for 15 minutes.

Left brain versus right brain theory

There’s a grain of truth to the idea that the right half of our brain governs creativity and the left half analytical thinking, but it’s a lot more complex than “creative people use their right brain and analytical people their left brain.” The most influential scientific study of brain hemispheres dates to the 1960s, when epilepsy researchers determined that, “for the most part, the left half of the brain outperformed the right in language and rhythm, while the right half was superior in discerning spatial orientation, emotion, and melodies.”

But since then, we’ve been able to observe brain activity more closely, and it indicates complex activities require communication between different parts of the brain. Brain research aside: If you consider the combination of creativity and analysis necessary to compose a symphony or devise a mathematical proof, the idea of one brain hemisphere being dominant starts to fall apart.

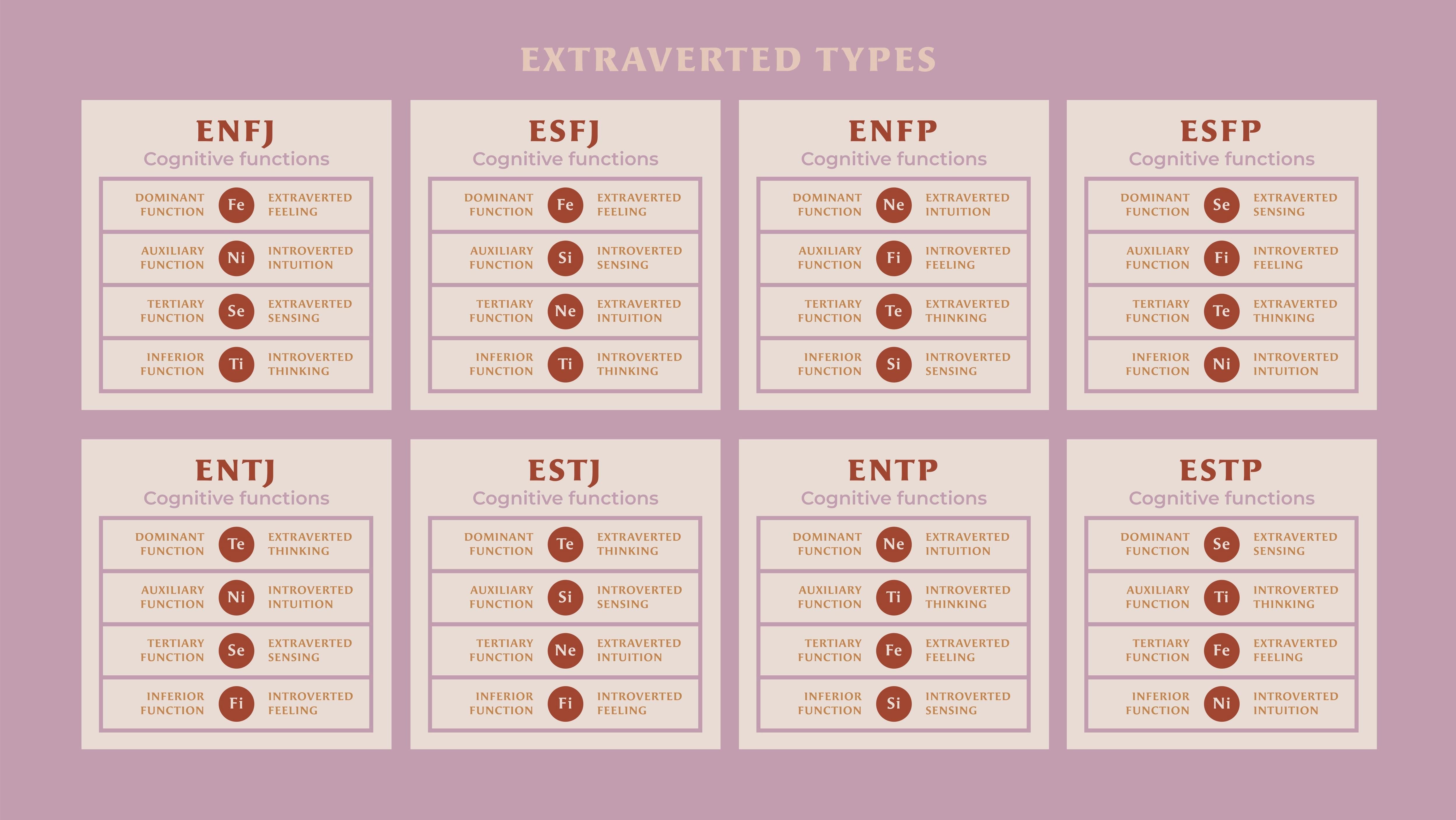

Myers-Briggs personality types

The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator categorizes people into 16 personality types based on answers to 93 questions like “Do you usually: A) Value emotion more than logic? Or B) Value logic more than feelings?” The test is taken by about 2 million people a year in academic and professional settings, and some organisations use the results when making hiring decisions. It is also largely bullshit — basically a more complicated version of a horoscope.

“For most people, the MBTI personality test is neither accurate nor reliable,” Jaime Lane Derringer, a psychologist at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, told Discover. “Personality traits, including the four measured by the MBTI, are normally distributed. That is, most people score in the middle, with few people scoring very high or very low on any trait.”

Analysis has shown that there is no predictive value in the test for satisfaction or competence at different kinds of jobs; other research indicates about half of test takers will receive different results if they take the test a second time.

The Stanford prison experiment

For the 1971 Stanford prison experiment, researchers set up a mock prison for undergraduate volunteers and assigned them roles of prisoner or guards in order to measure the effects of social expectations on behaviour. The “guards” and “prisoners” seemed to slip right into their roles, and a lot of people drew a lot of conclusions about the results. But in spite of how well-known the experiment became and how shocking were its conclusions, it was actually really, really stupid.

It was basically a reality show. The “roles” of the students were never actually “guard” and “prisoner.” They were “person being observed and filmed pretending to be a guard or a prisoner,” so their actions only tell us how undergraduates react to being placed in a long form theatrical improv exercise. Then there’s the matter of self-selection: 24 undergraduates who answer an ad seeking subjects who want to live in a fake prison for a couple weeks is pretty much the opposite of a random sample. There’s also the problem of replication: BBC ran a similar “fake prison” for a TV show in 2001 and not only did it not replicate the results, the guards proved ineffective and the prisoners soon took over the prison.

Neuro-linguistic programming

According to the NLP Centre, Neuro-Lingusitic Programming is a “set of models that allow someone to create cognitive behavioural change and build more resourceful states to achieve their goals.” This is done largely through understanding non-verbal communication.

There are a ton of life coaches who use the technique. It has been touted as a cure for everything from phobias to depression to allergies, and a diverse array of celebrities from Oprah Winfrey to Russell Brand reportedly use its techniques. But neuro-linguistic programming is probably a crock. A product of the 1970s “human potential movement,” there is little scientific basis for any of the claims of NLP. It is based on outdated and disproven theories of how the brain works, and critics say it would be more accurate to describe NLP as a cult than anything approaching a science.

Playing music for children makes them smarter

There is a cottage industry of products, from DVDs for toddlers to prenatal sound systems for fetuses, based on the idea that playing classical music for your child will make them smarter. Belief in the “Mozart Effect” was so widespread that, in 1998, Georgia governor Zell Miller mandated that mothers of newborns be given classical music CDs. But there isn’t much research to back up the claim.

While unborn children can hear and react to music in the third trimester of a pregnancy, there isn’t any indication it has any effect on well, anything. It’s the same for the born: Research just doesn’t show listening to classical music (or really any music) has a longterm effect on IQ. Listening to music might produce a fleeting boost to visual-spatial reasoning, but a 1996 study in the U.K. showed that school kids who listened to then-popular band Blur did slightly better on tests than kids who listened to Mozart. (Woo hoo!)

People have different learning styles

The idea that people have different “learning styles” is widely accepted among educators — a 2014 study showed that as many as 90% of educators believed in it. But maybe we don’t, and even if we do, it doesn’t seem to matter.

The most widely used system of determine learning style, the VARK test, breaks learners down into “visual, aural, read/write, and kinesthetic,” but attempts to use the test results to change teaching styles shows kids don’t actually do any better on tests geared toward their style. A study in the U.K. in which students could choose a “visual” or a “verbal” learning style indicated a similar lack of results.

“There’s evidence that people do try to treat tasks in accordance with what they believe to be their learning style, but it doesn’t help them,” Daniel Willingham, a psychologist at the University of Virginia, told The Atlantic.

Hypnosis can help you remember things

We hold a lot of misconceptions about how memory works, but the idea that if you can put people in a “hypnotic trance” they will remember things they wouldn’t have otherwise is a particularly persistent one. Studies have shown that not only hypnosis not make it easier to recall things, it makes people more confident in their false memories, and hypnosis may also cause false memories. Test subjects who were hypnotized and given a memory test performed no better than their non-hypnotized peers, but they were more confident that their wrong answers were correct. “How could I have remembered it wrong? I was hypnotized!” may be the thought process at work.

Talk therapy requires examining your childhood

We’re all familiar with the idea of a therapist hovering over a patient and proclaiming “tell me about your mother,” but “talk therapy” that focuses on traumatic childhood events is growing less and less common. The most studied, recommended, and widely used form of talk therapy right now is cognitive-behaviour therapy (CBT), a school that is largely unconcerned with digging deep into patients’ pasts to discover why they’re so messed up in the present.

Instead, CBT focuses on symptoms and leaves causes alone. If you’re nervous in social situations, CBT might teach you strategies for chilling out at barbecues as opposed to trying to make you talk about what happened at your fifth birthday party. While there’s no one-size-fits-all approach to psychological counseling, meta-analsyis of CBT research strongly indicates its effectiveness.

Dreams mean something

Many cultures believe dreams are prophetic. Freud believed dreams reveal our unconscious mind through symbolism. There’s no end of “dream interpretation” material out there. But these theories are probably all wrong. While it’s not possible to say for certain what the images our sleeping minds conjure mean, many neurobiologists think they don’t mean anything.

The Activation-Synthesis model of dreaming contends your brain fires randomly while you sleep, and you construct imagery from that. When you wake, you create a “dream story” around the imagery. It could be argued that the story you make up reveals something about who you are, but the dreams don’t mean anything by themselves.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.