Australia has recorded its first recession in 29 years — and the largest single-quarter fall in the country’s history. But it’s hard to contextualise this news without a bit of background information on what recessions are and how they impact your bottom dollar.

What is a recession?

There’s no single definition for ‘recession’, according to the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), Australia’s central bank.

Saying that, it’s usually defined as a continuous weak period in an economy and characterised by increasing unemployment rates, low household spending and safe business investments.

Commonly, a recession happens when there are two consecutive quarters of negative growth in real gross domestic product (GDP).

That’s something Australia hadn’t recorded in 29 years until the June 2020 quarter’s results were announced.

A depression is considered the next step in a faltering economy but, similarly, is loosely defined. If a recession continues for many consecutive quarters and worsens, something predicted to occur with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, it will likely be deemed a depression.

Why is Australia facing one?

In a word: COVID-19.

The combination of many businesses shutting down, drops in revenue and subsequent job losses means as an economy, we’re spending less. In turn, that affects the economy’s GDP as money stops shifting around at the rate it was pre-COVID.

To simplify the situation, what we are earning, we’re saving just in case, and that stops the economy from growing.

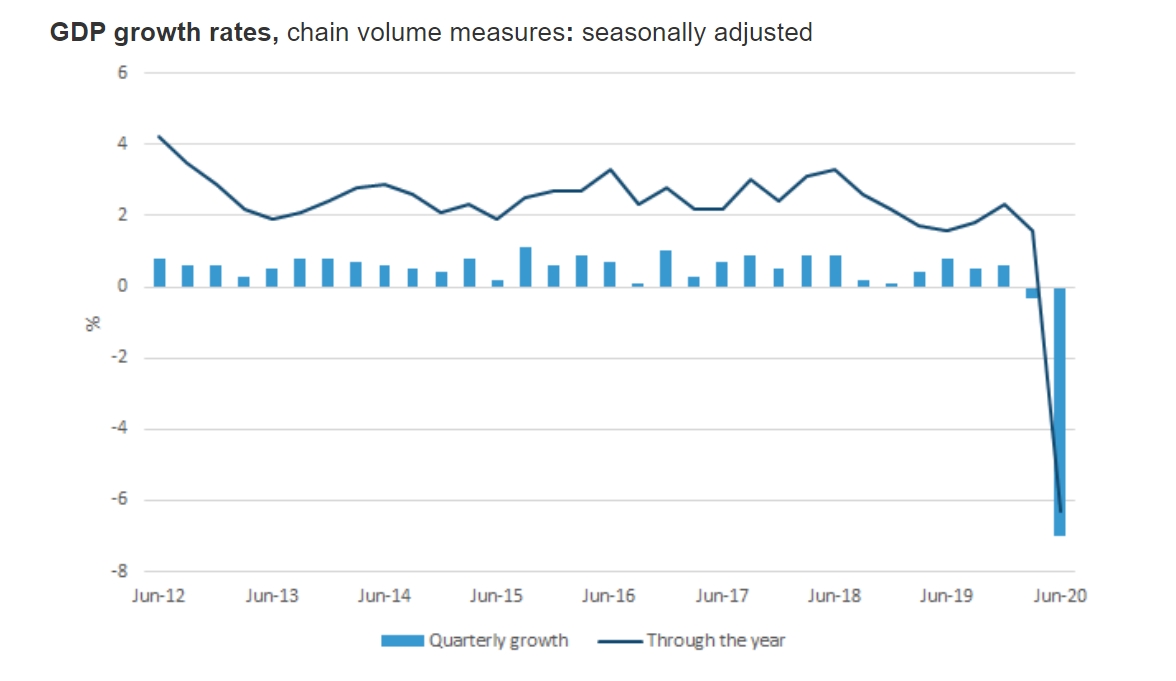

If you’re more of a visual learner, let this graph explain the recent situation:

It’s true that the country’s economy was already in a vice but a global pandemic — effectively stopping all tourism revenue among everything else — worked to deteriorate the situation at a far more rapid pace.

The 7% shrinkage in the economy over a three-month period marks the largest since the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) began recording this date in 1959. But it’s not the only time the country has faced dire times.

How many recessions have we had and how does this one match against them?

The RBA points out there have been three notable recessions, two depressions and the more recent Global Financial Crisis (GFC), considered a ‘downturn’ locally, in Australia’s history.

There were three major recessions during the 70s, 80s and 90s with unemployment peaking at around 11% during the latter. None of them can really be compared to the 2020 situation as a global health crisis wasn’t primarily to blame.

Australia’s last depression was the big one we’ve all heard about — the Great Depression of the 1930s. It lasted around two years but the recovery took a lot longer. At its peak, it’s estimated that the unemployment rate sat at a colossal 30%.

Prior to that, there was a major one during the 1890s, which was deemed far worse and likely led to the formation of unions and Australia’s Labor Party.

More of us will likely remember the GFC of the mid-2000s but Australia emerged from it relatively unscathed thanks to a strong government response and a bit of luck.

What do governments usually do in response to them?

How a government responds to a recession is particularly important. During the GFC, the government’s major increase in spending is credited as one of the reasons Australia largely escaped a recession still despite being hit.

There are usually two economic camps that determine the response to an economy under stress: austerity measures and Keynesian economics.

The first, austerity, is when government debt builds up as a result of providing monetary support to companies and sectors, and the government decides to put the brakes on spending in order to avoid defaulting on any loans.

It does this by three main levers: increasing taxes to generate government revenue; cutting government services it deems non-essential; and decreasing spending on projects or initiatives.

It’s typically viewed as a bad response and examples, such as Greece’s debt crisis, show it can have a particularly adverse effect on an economy, potentially even worsening it.

The other option is to essentially do the opposite. John Maynard Keynes, the father of Keynesian economics, suggested increasing government spending and lowering taxes to increase consumer confidence. By creating labour-intensive government projects and letting citizens keep more of their money, the economy would, in theory, be stimulated and recover quicker, providing a return on the government’s investment.

This was the Rudd Government’s approach to the GFC, providing stimulus packages that increased spending and kept the economy rolling. Coupled with Australia’s strong financial position as the crisis unfolded internationally, it was deemed the primary reason the country skipped the recession that affected the rest of the globe.

Of course, it’s hard to simply apply the same logic to 2020 where a much more obvious villain, coronavirus, remains a constant threat until a vaccine swoops in to save the day.

Australia’s first recession in three decades is a scary headline but what the future holds for our recovery is still in the works. Until then, like everything else right now, it’s really just a fortune teller’s guess.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.