Programmer Brannon Dorsey wrote up a fascinating and fairly technical piece about the perils of DNS rebinding the other day. It’s worth a read if you have even the slightest interest in how web browsers work to prevent one site — a scammy site, let’s say — from sending a request to another site — your bank — and draining your accounts or manipulating your credentials (without the site’s explicit permission).

Photo: Justin Sullivan (Getty Images)

His research mainly focused on how DNS rebinding could allow a malicious site (or person behind it) to muck with devices like your Google Home, Roku, smart thermostat, or router, to name a few.

As for the consequences, you might be dealing with more than just a website forcing your smart speaker to play the trololo song:

The Radio Thermostat CT50 & CT80 devices have by far the most consequential IoT device vulnerabilities I’ve found so far. These devices are some of the cheapest “smart” thermostats available on the market today. I purchased one to play with after being tipped off to their lack of security by CVE-2013 — 4860, which reported that the device had no form of authentication and could be controlled by anyone on the network. […]

That assumption turned out to be correct and the thermostat’s control API left the door wide open for DNS rebinding shenanigans. It’s probably pretty obvious the kind of damage that can be done if your building’s thermostat can be controlled by remote attackers. The PoC at http://rebind.network exfiltrates some basic information from the thermostat before setting the target temperature to [35°C].

That temperature can be dangerous, or even deadly in the summer months to an elderly or disabled occupant. Not to mention that if your device is targeted while you’re on [holiday] you could return home to a whopper of a utility bill.

Radio Thermostat CT50Photo: Amazon

While a number of the major device manufacturers Dorsey reached out to have some kind of patch or update on the way to prevent DNS rebinding attacks from working, you should also take a few steps right now to lock down your (likely) not-so-secure wireless router.

As Dorsey puts it: “I should mention though that I’ve largely stayed away from applying my DNS rebinding research to routers so far… Mostly because I’m almost too afraid to look ????.”

Change these settings on your router for stronger security

If your router came with any kind of default login for its web-based UI — and that’s probably not the case if you own a fancier mesh router that you set up using an app on your smartphone or tablet — that’s something you’ll want to change right now.

You should have already changed it, because nothing is more insecure than having a device that shares a common login and password with every other device the company makes.

If you’re typing “admin” and “admin” for your user name and password when logging into your router’s settings (either web or app-based), or something similarly generic, change both of those right now.

Now that you’re in your router’s settings menu, look for a section that deals with UPnP — this might be easily labelled within your router’s main settings menu, or it might be an option that’s buried in an advanced settings menu somewhere.

Do some digging (or consult your router’s manual) to find out where it is, if it exists. And once you find it, consider turning UPnP off. As Dorsey writes:

“These UPnP servers provide admin-like control over router configuration to any unauthenticated machine on the network over HTTP. Any machine on the network, or the public Internet through DNS rebinding, can use IGD/UPnP to configure a router’s DNS server, add & remove NAT and WAN port mappings, view the # of bytes sent/received on the network, and access the router’s public IP address (check out upnp-hacks.org for more info).”

Certain software you use — like gaming services or BitTorrent clients — might require you to forward ports on your router manually in order for them to work effectively. If you’re a heavy user of either, you might not want to trade security for convenience.

And if you just use your laptop to browse the web and chat with friends, you probably don’t need UPnP enabled. Worse comes to worse, you can always re-enable it if you find that its absence causes you (or your favourite apps) a lot of grief.

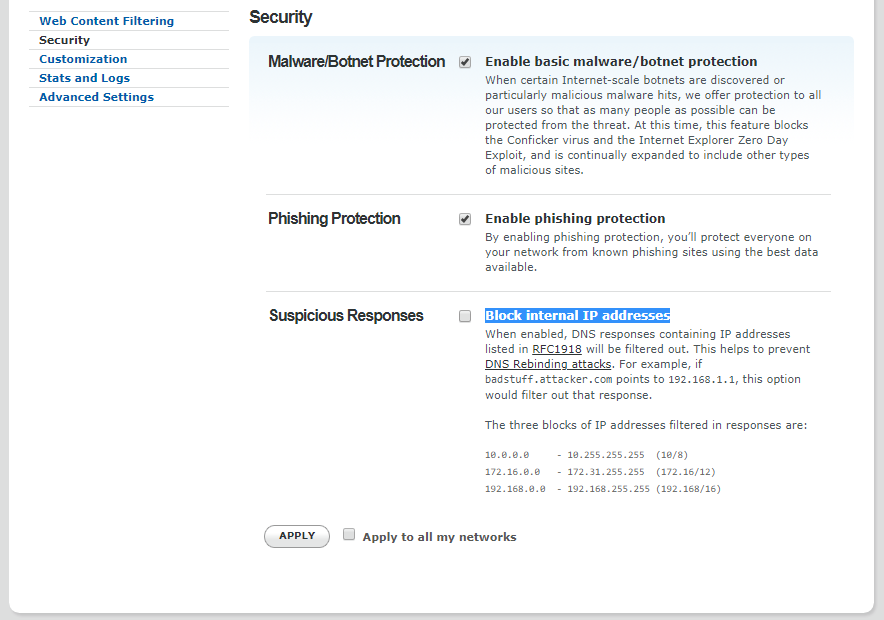

Dorsey also suggests switching your router’s DNS to a service like OpenDNS, rather than using your ISP’s DNS, as you can then use OpenDNS to filter suspicious IP addresses out of DNS responses.

Assuming you’ve gone through the process of opening up a (free) OpenDNS account, set up your router to use it and have installed OpenDNS’ software (for Windows or macOS), you’ll want to visit OpenDNS’ settings page and click on your network’s IP address.

From there, click “Security” on the left-hand sidebar and make sure “Block internal IP addresses” is checked. Check “Apply to all my networks” and click the Apply button.

Screenshot: OpenDNS

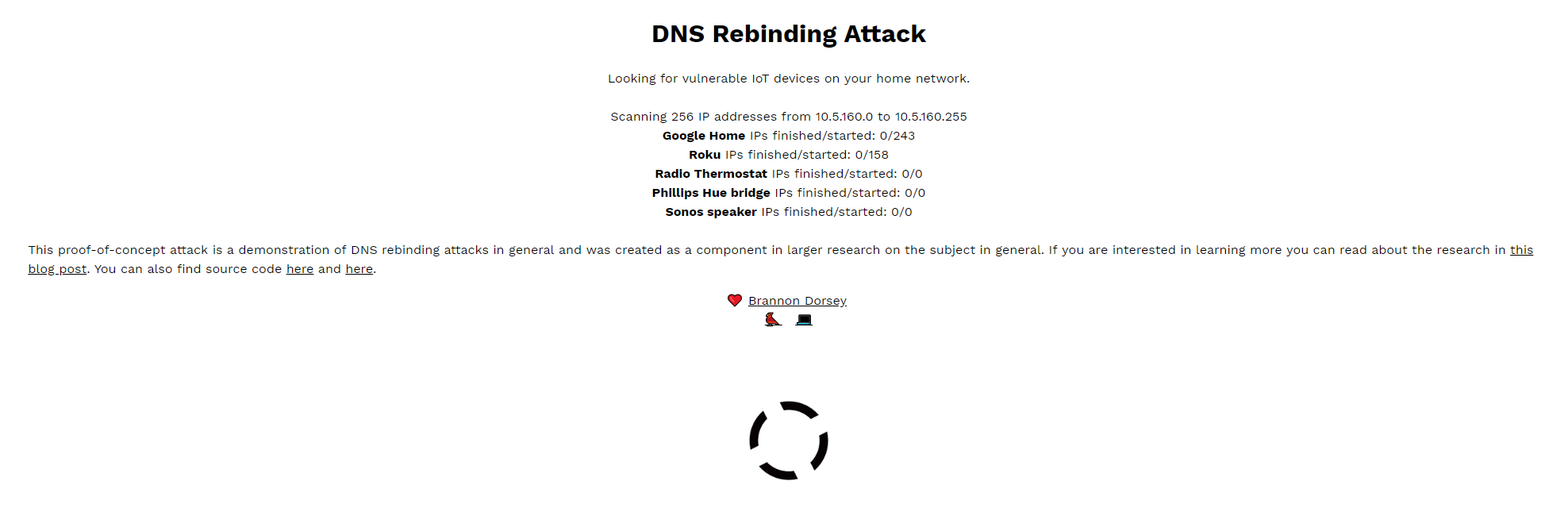

Once you’ve done all that, check out the website Dorsey created that can help you figure out if your connected “smart” devices are still vulnerable.

Screenshot: David Murphy (rebind.network)

Comments