Despite its quirky humour and overly lit sets, The Good Place manages to tackle some of the biggest moral quandaries life has to offer each episode by teaching lessons with some very real philosophy. Watching through it, I can’t help but feel like the show makes for an excellent, if basic, intro to moral philosophy class. Here are a few examples of important concepts you’ll learn from the show.

Image via NBC/Universal.

The Good Place is an American fantasy comedy series about the afterlife created by Michael Schur. Originally screening on US television network NBC, the show is now available to watch on Australian Netflix. Here are some of the lessons the show teaches you.

[referenced url=”https://www.lifehacker.com.au/2017/10/what-it-means-to-be-awesome-according-to-a-philosopher/” thumb=”https://i.kinja-img.com/gawker-media/image/upload/t_ku-large/gbkbu7vagwfgjhshp0bm.gif” title=”What It Means To Be Awesome, According To A Philosopher” excerpt=”At some point in your life you’ve probably said that someone is either awesome or that they totally suck. I know I have. But what does that mean in a philosophical sense? One philosopher thinks it’s all about open mindedness in social situations.”]

Being ‘Good’ Is Something You Learn and Must Practise

What does it mean to be “good”? Are some people just born bad seeds? I’m going to spoil the premise of the first episode for you here, but it’s OK, the Netflix description does the same thing. Basically, Eleanor (Kristen Bell) dies and wakes up in the afterlife. She’s told that she lived an ethically sound life and that she made the cut for “The Good Place”. But there’s a problem: Eleanor has been mistaken for someone else and doesn’t belong there. She was a terrible person in life and belongs in the so-called “Bad Place”. She tries to play it off, but soon realises she needs to come up with a plan or everyone will know she’s an impostor.

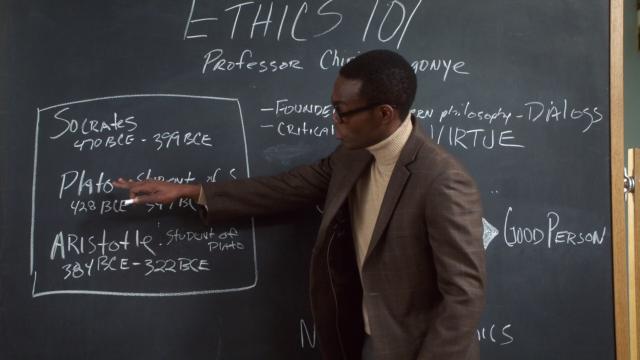

Fortunately, she finds help in her assigned soulmate Chidi, who was a professor of moral ethics in life. Through some private tutoring, Eleanor begins to learn something everybody should know: Being “good” is a choice you make. As Aristotle put it, your character is voluntary, so nobody is born “good” or “bad”. You have to decide which you want to be. Chidi explains that not only is it possible to shake one’s nature of being selfish and inconsiderate, it’s possible to change one’s ways and put others ahead of yourself. The change can’t happen overnight, of course, but learning to be “good” is possible – as long as you practise. Being good to others is a habit just like any other, and practise is what helps you pursue perfect (though you’ll never reach it).

Doing ‘Good’ Things Doesn’t Necessarily Make You a Good Person

In The Good Place, the version of the afterlife you get sent to is based on a complicated point system. Doing “good” deeds earns you a certain number of positive points, and doing “bad” things will subtract them. Your point total when you die is what decides where you’ll go. Seems fair, right?

Despite the fact The Good Place makes life feel like a point-based video game, we quickly learn morality isn’t as black and white as positive points and negative points. At one point, Eleanor tries to rack up points by holding doors for people; an action worth three points a pop. To put that in perspective, her score is -4008 and she needs to meet the average of 1,222,821. It would take her a long time to get there but it’s one way to do it. At least, it would be if it worked. She quickly learns after a while that she didn’t earn any points because she isn’t actually trying to be nice to people. Her only goal is to rack up points so she can stay in The Good Place, which is an inherently selfish reason. The situation brings up a valid question: Are “good” things done for selfish reasons still “good” things?

I don’t want to spoil too much, but as the series goes on, we see this question asked time and time again with each of its characters. Chidi may have spent his life studying moral ethics, but does knowing everything about pursuing “good” mean you are? Tahani spent her entire life as a charitable philanthropist, but she did it all for the questionable pursuit of finally outshining her near-perfect sister. She did a lot of good, but is she “good”? It’s something to consider yourself as you go about your day. Try to do “good” things, but ask yourself every once in a while who those “good” things are really for.

[referenced url=”https://www.lifehacker.com.au/2017/10/just-being-good-isnt-enough/” thumb=”https://i.kinja-img.com/gawker-media/image/upload/t_ku-large/ms4n5mxafp2ew7ax1vn2.jpg” title=”Just Being ‘Good’ Isn’t Enough” excerpt=”Welcome back to Mid-Week Meditations, Lifehacker’s weekly dip into the pool of stoic wisdom, and how you can use its waters to reflect on and improve your life.”]

Morality Is Ambiguous

Now, you’ve probably noticed that I’ve been putting the words “good” and “bad” in quotation marks the whole time (it’s probably driving you nuts). That’s because “good” and “bad” are subjective, making them almost impossible to define. A lot of things you might consider “good” could actually be considered “bad” to someone else who has a different perspective. The Good Place is always addressing that line, and it’s an important issue to tackle, especially for those who are brought up being told there is a definitive version of right and wrong. While you watch, you slowly begin to understand that morality is a collective social decision, and it can vary depending on what social circle you’re in.

As Chidi often explains, most ethical morality falls into a “grey area”, where intent, scenario and other variables can change the way people feel about things. At one point, Chidi is forced to literally attempt the famous “trolley thought experiment”, where he must decide whether or not to kill one person to save five. The common “greater good” answer is to change the track so that only one person dies and five people live. But there are always variables in the real world. What if the one person is a child? What if the five people are dressed as Nazis? What if you know one of the people? Or, what if you sit back and do nothing? Is it “good” to be a bystander? As soon as the experiment becomes real, Chidi, a man who spent his entire life studying moral ethics, falls apart. There is no morally sound answer to the thought experiment. In fact, there are rarely, if ever, morally sound answers in the real world.

I’m sure some of you are thinking, “No, some things are just wrong. Killing is wrong!” But if you are, you’re missing the point. Discussing morality the way The Good Place does isn’t about redefining basic moral tendencies like we see in law and religion – it’s about learning how to look at them from the outside. Through clever jokes and silly plot twists, the show gives you a better understanding of the true ambiguity of morality, while also subtly teaching you to look at why something is the way that it is.

Comments

One response to “What Netflix’s The Good Place Can Teach You About Morality”

I’m currently studying an ethics course and the first thing you learn is, it is sometimes very very hard to work out what is the “best” answer. ie the trolley experiment often is answered with people switching tracks ie save five and kill one but the same question phrased differently ie five people with organ failure can be saved if you sacrifice one healthy person suddenly gets a no response ie let the five die and keep one alive.