Calorie/kJ counts are front-and-center on treadmill screens, food labels, and even restaurant menus. But if you’re trying to lose weight (or just monitor how healthily you’re eating), those numbers can be misleading.

Photos by Paul Papadimitriou, Joe Loong, E. Dronkert, and João Trindade.

You need to create a calorie deficit to achieve weight loss; that’s clear. But the calories you adjust via diet and exercise are impossible to measure exactly. You’re working with estimates, not precision calculations. That 2020-kilojoule fast food burger is probably in the ballpark of 2000 kilojoules, but you can’t budget down to those last 20 kilojoules, or maybe even those last 200. Here’s why.

First, a clarification. Calories and kilojoules are just a measure of energy in a raw physics sense: if you set a high-calorie food, like Doritos, on fire, you will get more total heat out of that than if you set a low calorie food on fire, like a (dehydrated) baby carrot. Inside your body, the same chemical reaction happens as in a fire: carbohydrates, fats, and proteins react with oxygen to form carbon dioxide (which you breathe out) and water. Your body does it through hundreds of careful chemical reactions, and fire does it with fire, but at the molecular level it’s the same idea.

Which is why we need to stop using phrases like “are all calories the same?” and “it’s the kind of calories you eat that matter.” That’s like saying “Here’s a kilogram of groceries, but what kind of kilograms are they?” Calories, like kilograms, are just a measure of how much.

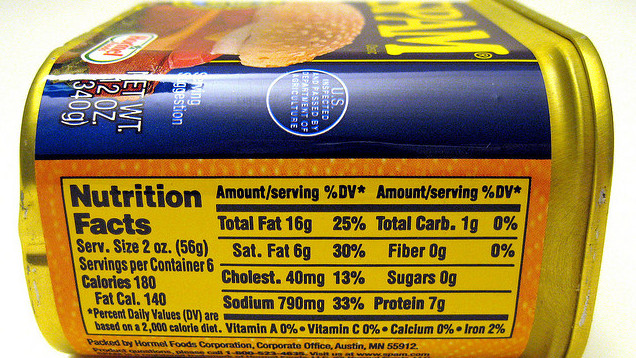

Food Labels Are Never 100% Accurate

If you track the calories you eat, you’ve probably noticed how difficult it is to count calories when you’re cooking at home. We’re also bad at eyeballing portions (even the experts get it wrong). But just because you have a package with a definite calorie count listed doesn’t mean you’ll actually get that exact amount of usable energy in your body.

At a 2013 meeting of the American Academy for the Advancement of Sciences, an expert panel pointed out many of the flaws in calorie counts:

[The experts] agreed that net caloric counts for many foods are flawed because they don’t take into account the energy used to digest food; the bite that oral and gut bacteria take out of various foods; or the properties of different foods themselves that speed up or slow down their journey through the intestines, such as whether they are cooked or resistant to digestion.

Cooked foods tend to yield more calories than raw foods, which labels sometimes get wrong. The numbers on labels come from calculations using “Atwater factors,” developed more than a century ago by comparing the burnable-with-fire energy in food compared with the energy in the output, including feces, of people who had eaten that food. Not surprisingly, food manufacturers use the numbers from those studies rather than repeating the experiments with each new formulation of their product.

Processing matters, too. Some more of those intrepid researchers fed volunteers peanuts in different forms, and found that they weren’t equally digested, writing: “With whole nuts, 17.8% of the lipid load [in other words, fat calories] was lost in the stool, whereas values were 7.0% and 4.5% for peanut butter and peanut oil loads, respectively.”

Similarly, when a group of researchers investigated the calorie value of raw whole almonds, they found that the standard listing for almonds overestimated calories by 32%. It may be more accurate, according to nutrition writer David Despain, to consider the calorie label to be, not the exact, but the maximum number of calories you might get out of that food.

What You Eat And What You Burn Don’t Always Add Up

Sure, in a thermodynamics sense the calories have to go somewhere. But you can’t always see or control your energy burn, certainly not down to the single-calorie level.

The oft-repeated calculation is that 3,500 calories adds up to a pound (half a kilo) of fat, so if you eliminate that many calories from your diet (or burn the equivalent in exercise), you’ll lose that amount in weight. Similarly, take in 7000 extra calories and you’ll gain a kilogram. That’s simple on paper, but not so simple in real life. When researchers in the US tried to make volunteers gain 16 pounds by feeding them an extra 1,000 calories every day for eight weeks, they ended up gaining anywhere between 3 and 15 pounds. Clearly, the extra energy went somewhere, apparently fidgeting (scientifically termed Non Exercise Activity Thermogenesis — in other words, ways you move around when you’re not purposely exercising).

The way you eat can also affect the calories you burn just by being you (technical term: Resting Energy Expenditure). Research published in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that people on a low fat diet burned fewer calories at rest than people on a high fat diet.

Digesting food itself burns energy, and this seems to depend on how processed the food is, and how much fibre is in it. In one delicious-sounding experiment published in Food & Nutrition Research, people who ate a grilled cheese sandwich made with cheddar cheese and whole-grain bread burned more calories to digest it than did people who ate the same sandwich made with white bread and Kraft singles.

There are other places that energy might go. Research in both mice and humans, published in Science, shows that the microbes that live in your gut may influence how much fat you store, without a difference in the calories you eat.

Calorie Burn Estimators Aren’t Always Right, Either.

How many calories did that workout burn? The numbers you can look up are based on weight, time, and some vague descriptions of activities. Yesterday’s workout and today’s workout might feel different to you, but maybe they’d both fall under “weight lifting, vigorous.” Or maybe “weight lifting, general.” It’s not clear how to choose.

Your real calorie burn, of course, depends on the particulars of your workout and the particulars of your body. Some runners are more efficient than others, burning fewer calories to do the same work. That’s great for them — it means they’re faster, or they can run farther — but if you and a super efficient runner were to go for a jog together, you’d burn different numbers of calories.

Do you fare any better with a gadget that bases calorie burn on your heart rate, as many fitness trackers do? Evidence suggests they’re better, but not perfect. A study published in the Journal of Sports Science & Medicine found that a Polar heart rate monitor (the 810i) and a SenseWear armband were less accurate at lower intensity rowing exercises than at moderate intensity, and that the readout from the rowing machine itself was significantly too high.

Another, published in Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, found that the Polar 410S gave a fairly accurate calorie burn for men, but overestimated women’s calorie burn in cycling, running, and rowing by about 2 calories per minute. That’s a difference of 60 calories for a 30-minute workout, or to put it in food terms, two pats of butter or half a can of Coke.

Fitness trackers claim to use multiple sensors to figure out your activity, but it’s hard for them to detect and calculate everything correctly. Fitbit states on their website that their device is “optimised for walking, running, and general household and lifestyle activities” and less accurate for other activities like cycling.

What to Do Instead

The situation isn’t hopeless, though. If you still want to create an energy deficit (or an energy excess, for those trying to gain weight), here’s how to take advantage of what we do and don’t know about calories:

- Let go of the idea you can track your intake and output down to the single-calorie level. You just can’t.

- Use food labels as a maximum, but know you may be getting fewer calories in some cases.

- Eat less-processed foods, especially with fibre, if you’re trying to reduce calories. You may be eating fewer calories that way, and burning more to digest.

- Continue to keep a food diary for mindfulness. It can give you an idea of how much you’re eating, since the calorie count will be roughly correct (a day you eat a dozen doughnuts will be higher than a day you just have salads) and all the while it makes you think about what you’re putting into your mouth. That aspect can be kind of crazy-making for some of us, and if your diet isn’t broken there’s no need to track it or fix it. There may be some benefit to checking in with a short-term food diary every now and then, to make sure you’re eating well, even if you don’t have the mental energy to track all your food all the time.

So even though you can’t know your calorie intake and calorie burn down to the last decimal place, you can still work in broad strokes to balance your food and exercise to come out to something that works for you. If tracking calories helps you make better choices in the big picture, it’s a tool worth using.

Comments