B.F. Skinner gave us concepts like “conditioned behaviour”, “positive reinforcement” and even “time-outs” for children. But he was also a radical among psychologists who cast aside notions of dignity and free will. Here’s why Skinner continues to be relevant — and even a bit dangerous.

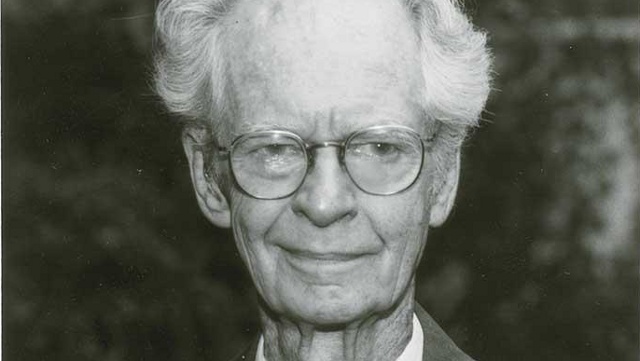

Though not as famous as some of his forebears and contemporaries, such as Sigmund Freud, Ivan Pavlov and Jean Piaget, Harvard psychologist B.F. Skinner (1904-1990) forever changed the way we study and understand human behaviour. His legacy reaches far and wide, influencing and inspiring such domains as child-rearing, experimental psychology, behavioural therapy, management, education and self-help.

Dangerous Ideas

Ultimately, however, his most cogent contribution to psychology is the understanding that what we do is largely a function of the consequences of our behaviour. Thoughts, emotions and actions, said Skinner, are exclusively products of the environment. His behaviourism was a deterministic behaviourism, one that considered free will an illusion — an assumption that inspired him to write Walden Two, a book that described a utopian and quasi-totalitarian society predicated on the principles of positive and negative reinforcements.

What’s more, he grossly underplayed the role of biology in forging and regulating human behaviour, dismissing the burgeoning fields of behavioural genetics, evolutionary psychology and cognitive science. Skinner argued that humans don’t really think — that they merely respond to environmental cues. He came up with various therapeutic techniques, including “operant conditioning”, which, while beneficial for the treatment of disorders like phobias and addictions, have proven extremely problematic for the “treatment” of autism and homosexuality.

Taken together, it’s clear that his ideas — if applied in the way he envisioned — would likely cause more problems than they would solve. But not to throw Skinner out with the bathwater, many of his ideas continue to be helpful and even insightful given the biases of current times.

Environment is Everything

B.F. Skinner emerged at a time when Freudian psychoanalysis was flourishing. Going against the grain, and building upon the theories of Ivan Pavlov and John B. Watson, he put forth some of the most elegant and concise theories on animal and human behaviour seen to that point.

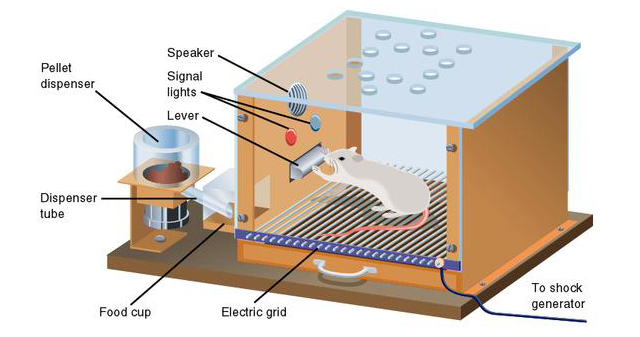

His studies on the connection between stimuli and observable behaviour in rats led to his famous Skinner Box — an enclosure equipped with levers, electrified floors and food pellets allowing for the precise measurement and control of experimental conditions (Skinner actually hated the term “Skinner Box”, preferring instead “Operant Conditioning Chamber”. This is also not to be confused with his so-called Baby In A Box — temperature controlled enclosures in which babies were placed for training purposes and to ease the burden on parents).

His animal research was predicated on the importance of consequences, especially rewards and punishments. By breaking tasks down into smaller and smaller parts, and rewarding success on those parts, he was able to facilitate behavioural change in animals, including those that weren’t “natural” or instinctual (like ping pong playing birds and piano playing cats). He was so successful in this that he managed to convince the military to fund his research, namely Operation Pigeon — the idea of training pigeons to guide bombs and torpedoes.

Skinner argued that humans were no different — that they could be trained through the delivery of new subject matter in a series of graduated steps with feedback at each stage. Changes in behaviour, said Skinner, were simply the result of a person’s response to events occurring in their environment. Nothing more, nothing less. This could apply to everything from the way we define a word, the way we perceive a spider or how we go about solving a maths problem.

“The strengthening of behaviour which results from reinforcement is appropriately called ‘conditioning’,” wrote Skinner in his 1953 book, Science and Human Behaviour. “In operant conditioning we ‘strengthen’ an operant in the sense of making a response more probable or, in actual fact, more frequent.”

It sounds exceedingly simple, but it’s a theory that did much to explain seemingly anomalous and counterproductive behaviours. Take gambling addiction, for example. By using mice, he demonstrated why we ourselves might be inclined to repeatedly pull on a lever. Where a Skinner Box may be configured to deliver a tasty morsel to a rat, a one-armed-bandit likewise delivers the promise of a reward. Both “systems” offer positive reinforcement on what’s called a variable ratio schedule — a reward which occurs with regular frequency, such as one in about every eight pulls. It’s enough to produce in a high response rate, and subsequently, a conditioned behaviour.

Psychologist Mark Sherman described Skinner’s contribution to behavioural psychology this way:

The principles that Skinner demonstrated and defended so well work all the time, whether or not they are being used intentionally, say by parents or managers or — as is most often the case — unintentionally, in the everyday life of all living organisms. The basic principle of reinforcement (and punishment) — which states that the frequency of a behaviour is strongly affected by its immediate consequences — is necessary for us to survive and flourish. It can help to explain how we learn almost any skill and how we learn not to touch hot stoves; and it can explain (or at least help to explain) why a kiss can be the first step toward a long and happy marriage.

Indeed, his theories could also help explain both beneficial and detrimental behaviours, like staying in a loveless relationship, overeating, smoking and drug abuse.

‘The Real Question Is Whether Men Think’

But while Skinnerian psychology has proven necessary for any meaningful discourse on human behaviour, it’s also grossly insufficient.

Take his work on child development and the emergence of verbal behaviour. Skinner argued that imitation was a serious mechanism for the acquisition of language. Verbal behaviour, he said, was learned by an infant from a verbal community. This overly simplistic explanation attracted the ire of linguist Noam Chomsky, who (arguably) launched the cognitive psychology movement by virtue of his response. Among other things, Chomsky argued that many of Skinner’s animal experiments could not be applied to humans and that he never fully developed a science of behaviour.

Skinner, for his part — and for the duration of his entire career — actively denied the veracity of related disciplines. He hated “mentalistic psychology”, what we today refer to as cognitive science. He perceived it as being far too reductionist and off course, while simultaneously arguing that it was nearly useless for making predictions and testing in environmental settings.

And in regards to the relation of mentalism to the issue of artificial intelligence — a discipline largely predicated on the notion of cognitive computationalism — Skinner remained sceptical.

“The real question is not whether machines think but whether men do,” he wrote, “The mystery which surrounds a thinking machine already surrounds a thinking man.”

And in his 1974 book, About Behaviorism, he wrote:

When what a person does is attributed to what is going on inside him, investigation is brought to an end. Why explain the explanation? For twenty five hundred years people have been preoccupied with feelings and mental life, but only recently has any interest been shown in a more precise analysis of the role of the environment. Ignorance of that role led in the first place to mental fictions, and it has been perpetuated by the explanatory practices to which they gave rise.

But Skinner didn’t stop there. He also railed against the emerging science of behavioural genetics and sociobiology. In his papers “Selection by Consequences and “A Matter of Consequences”, he argued that such scientists were wrong to suggest that there were genes for specific behaviours, such as altruism or a predisposition to certain addictions. Genes, said Skinner, simply played a minor role relative to larger processes at work. He proposed that humans have genes which are pre-programmed for operant conditions. Skinner took the Blank Slate hypothesis to an extreme.

In regards to altruism, for example, he argued that the question of whether or not a person will act to help another in a given situation is dictated by the culture — and not some inborn trait designed to perpetuate and advance the human race.

People don’t shape the world, said Skinner, it shapes them.

Skinner’s dismissal — or underplaying, at the very least — of both cognitive science and genetics seems a bit misguided by today’s standards. No doubt, while the learning process and behavioural conditioning are undeniably important, it’s becoming exceedingly obvious that genetic predispositions do exist, and as the neurosciences are increasingly showing, our brains are highly specialised and modularised for certain tasks — our psychologies and behaviours included.

British writer and graphic novelist Alan Moore put it well when he said,

B. F. Skinner actually put forward — and this is a measure of scientific desperation over consciousness — the idea that consciousness was a weird vibrational by-product of the vocal cords. That we did not actually think. We thought we thought because of this weird vibration caused by the vocal cords. This shows the lengths that hard science will go to to banish the ghost from the machine.

‘Give Me a Child and I’ll Shape Him Into Anything’

In addition to setting aside science that would do much to compliment his work, Skinner also dabbled in some suspect politics and sociology. Given his “benign totalitarian” leanings, we can be thankful that he never took office or found himself in a position where he could apply his self-described “technology” on the masses.

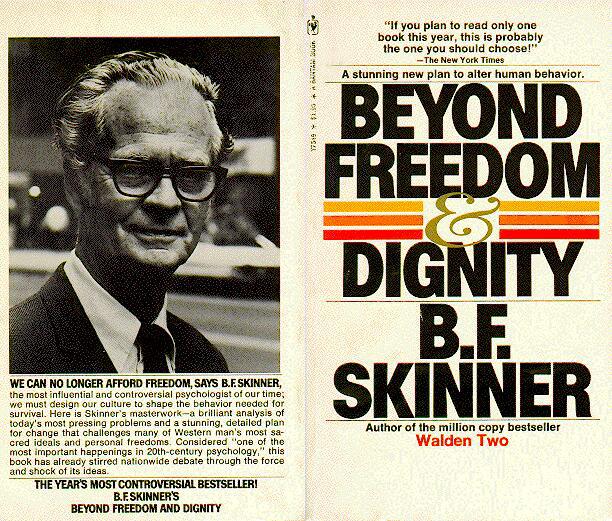

Indeed, Skinner’s thinking was quite distant from what’s regarded as humanistic psychology. Just take the title of his 1971 book, for example: Beyond Freedom and Dignity. In it, he made the case that behavioural psychology could solve all the world’s problems. But he doubted that people would ever have the inclination to use this tool.

Earlier, Skinner’s 1948 novel Walden Two envisaged utopian societies or intentional communities resulting from tightly controlled systems in which people were motivated solely by the manipulation of positive and negative reinforcements. It’s an idea eerily reminiscent of the Soviet Union’s use of psychiatry to suppress political dissent. Indeed, the notion of conditioning the population to conform to a predetermined set of behavioural standards is an undeniably dystopian notion.

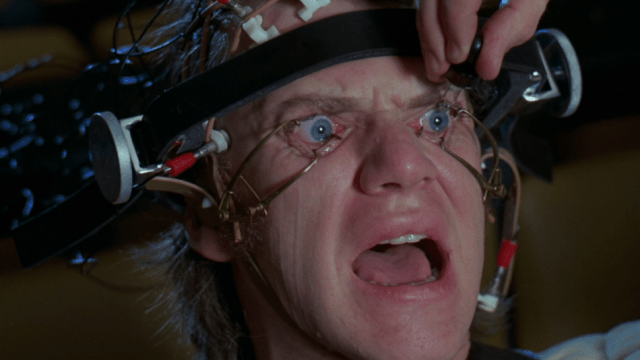

Which all leads to another fundamental problem intrinsic to Skinner’s radical behaviourism: Not all psychological conditions or states of mind can or should be conditioned. Take autism, for example. Many people in the autistic rights movement argue that the most common therapies for autism are unethical. Abusive, even. Indeed, therapists sometimes use aversion therapy, including shock therapy and restraints, when trying to “condition” or “train” children out of their autism. But as scientists are learning, it’s not a matter of positive and negative reinforcements — autistic brains are simply “wired” differently.

Relatedly, Skinner’s ideas have been adopted by “conversion therapists” working to change the sexual orientation of homosexuals to hetereosexuals. Years ago, therapists tried to deter homosexuals’ desire through the use of electric shocks and nausea-inducing drugs while displaying same-sex erotic images. More recently, conditioning techniques include masturbatory reconditioning, visualisation, social skills training and convincing males to adopt traditional masculine gender roles, such as participating in sports, interacting with heterosexual men and fathering children. (See Joseph Nicolosi’s Reparative Therapy of Male Homosexuality as an example of this pseudoscientific nonsense). Like autism, there’s no place for re-conditioning in this arena.

A Flawed But Lasting Legacy

But this is not to deny the efficacy of Skinnerian behavioural therapy when performed in the proper contexts. While his strict form of behavioural therapy isn’t widely practised anymore, a variation of it lives on in the form of cognitive-behavioural therapy.

It’s proven useful in the treatment of certain pathologies, including simple phobias, anxiety disorders (like post-traumatic stress disorder and panic disorders) and addiction. It also works reasonably well for depression; as noted by psychologist Aaron T. Beck, depressed people think the way they do because their thinking is biased towards negative interpretations. Cognitive-behavioural therapy helps people reframe their world and become aware of their reaction to certain events. And when used in conjunction with antipsychotics, it can even help in the treatment of schizophrenia.

The cognitive-behavioural approach has proven useful as therapists have increasingly moved away from outdated Freudian psychoanalytic theories and towards more behavioural analyses as they pertain to cognitive phenomenon.

Moreover, in this era of nearly hysteric genetic determinism, it’s good to be reminded of the power that the environment holds in shaping our personalities. As far as the nature versus nurture debate goes, the pendulum has now swung too far in the opposite direction, the result of the tremendous genomic breakthroughs that are now commonplace. But it’s time to pull that lever back a bit and re-consider the ways our society moulds our preferences and tendencies.

Other sources: American Psychological Association [Psychology Today | New York Times.]

Comments