If you grew up in the 1990s, you practically absorbed a degree in AIDS studies just by existing — or at least that’s what it felt like. The years since then have brought better tests and treatments, and we now know more about the virus, but that information isn’t common knowledge. HIV and AIDS have fallen off our radar.

Illustration by Tara Jacoby.

Of course, it pops up every now and then, like when Charlie Sheen recently announced that he is HIV-positive. And many articles like this one are posted around World AIDS Day each year (responsible for the red spikes in this Google Trends chart).

Not everybody has the luxury of forgetting about HIV and AIDS. In Africa, nearly 25 million people are living with the virus. In Asia, teenagers’ AIDS-related deaths are actually on the rise. And it’s a known issue in the gay dating scene: Gawker’s own Rich Juzwiak has written about his experience here.

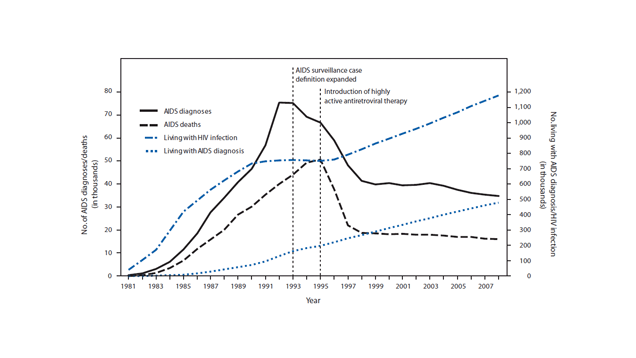

“There is still an HIV epidemic, and it remains a major health issue for the United States,” reads a bolded statement in the latest version of the US National HIV/AIDS Strategy. There are 50,000 new diagnoses in the US each year, and 1000 new HIV diagnoses in Australia. The diagnosis rate has held steady since the mid-1990s in the US, according to the CDC. It has also held steady in Australia over the past few years, so the number of people living with HIV continues to rise.

What Happened to AIDS?

AIDS is no longer a plague or a panic, thanks to a variety of advances: better treatments for HIV mean that it rarely progresses to AIDS. People who get tested can find out their status sooner, thanks to better tests, and people seem to have better awareness of the dangers of unprotected sex.

AIDS is just an advanced stage of HIV infection. Today, only about 2 per cent of people with HIV have AIDS. But in the 1980s and 1990s, says Dr Michael Kolber, director of the Comprehensive AIDS Program at the University of Miami, people with HIV tended to be diagnosed only when their infection was more advanced.

“We have all the tools we need to make HIV go away,” Dr Kolber says. But not enough people get tested, either because they don’t know they should, or because they can’t access the tests. Those that do find out they’re positive sometimes can’t or won’t take the medicine that keeps the virus in check.

That’s why public health groups, including the US government’s Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, run lots of initiatives to bring testing to more people, make medications more affordable and available and improve people’s understanding of the disease. In that spirit, here are some things you might not know about HIV, but probably should.

You Should Probably Get Tested

Currently, an estimated 27,150 people in Australia have the virus. And 12 per cent of the people infected don’t know they have it.

If you’re HIV positive, knowing your status puts you at a huge advantage. You can start treatment before you ever experience symptoms of infection, making you far less likely to develop serious illnesses, including the ones associated with AIDS. Treatment also reduces your chances of passing on the virus to others. Once you know your status, you can let your sexual partners know that they should get tested, and then they too can reap the benefits of early treatment.

In case you need a refresher: The virus can be transmitted through body fluids including blood, semen and pre-ejaculatory fluid, vaginal and rectal secretions and breast milk. You are not likely to get HIV from saliva, tears or sweat. This fact sheet gives a rundown of transmission routes, including scenarios like kissing where transmission is very rare but technically possible.

Everybody from age 13 to 64 should be tested at least once in their lives, according to the CDC. Once-a-year testing applies to anyone with risk factors, including having sex with people whose HIV status you don’t know, and depending upon how high risk you are you could need to test up to four times per year.

Testing technology has come a long way, says Gerry Schochetman, senior director of diagnostics research at Abbott Laboratories. (Abbott makes HIV tests.) Older HIV tests detect antibodies, which the human body makes in response to the virus. It takes weeks to months to make enough antibodies to show up on the test. Newer combination tests detect antibodies plus the virus itself, and this is the type the CDC recommends. Combination tests can detect HIV within a month after infection, and often sooner.

You can ask your doctor for a test, go to a rapid test clinic or visit a sexual health clinic. Sexual health clinics are free and confidential.

If one of those tests turns up positive, Schochetman says, you’ll be offered another type of test to confirm the diagnosis, and typically referred to counselling to help you understand your diagnosis and what you can do to avoid putting others at risk.

You should also be referred to an HIV specialist so you can begin to get treatment, even if you aren’t experiencing symptoms yet.

HIV Isn’t a Death Sentence, But It’s Not a Cakewalk Either

HIV is manageable with timely, consistent treatment: the amount of virus in an infected person’s blood can drop to undetectable levels, and the life expectancy of someone with HIV can be as long as that of someone without.

But not everybody gets on board with the treatment regimen. “Young people don’t like to take medicine when they’re healthy,” Dr Kolber says. Some would-be patients are afraid of the drugs’ side effects, but other factors contribute to the dismal percentage of people with HIV infections who are getting proper care: things like poverty, racial disparities and homelessness. “If you have services to support you such as housing, you’ll take your meds better than if you didn’t,” Kolber says.

Other health conditions can also interfere with care. Mosaic recently profiled several HIV patients from the UK, none of whom had an easy life. One, named Hugh, avoided seeking treatment at first, and then found that he couldn’t swallow the pills. Later, depression kept him from taking his medication, and with his immune system damaged, he contracted a toxoplasmosis infection that resulted in a seizure and lymphoma that required chemotherapy. He now lives with his parents and walks with a cane. He is 35.

The drugs that treat HIV are expensive — roughly $US2000 ($2682) a month in the US, Kolber estimates. A list of the drugs and their costs can be found here; most do not have a generic equivalent. In Australia, the cost is subsidised by Medicare, however even if you do not have access to Medicare there are other options available. A person will generally take three or more drugs as a “cocktail”, sometimes combined into a single pill, but exactly which drugs they take will depend on the particular strain of the virus they have.

The drugs also have side effects, which can become serious over time since people are (ideally!) taking the drugs for decades on end. Keeping up with medical care isn’t just about keeping HIV in check; it’s also to monitor whether the drugs are still working, and whether they are doing damage to your body. That can include, for example, liver damage and osteoporosis.

Medications Can Prevent HIV Transmission

Amazingly, there is a pill that an HIV-negative person can take to reduce their chance of contracting HIV by a whopping 99 per cent. It’s called Truvada and costs $10,000 per year. Unfortunately Australian trials are still being conducted, and even if successful we’re a few years off it being on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme.

HIV treatment itself is also a form of prevention. If you have HIV but are taking your drugs as directed, your chance of transmitting the virus is reduced, as much as 96 per cent depending on the study.

Treatment can get your viral load undetectable, so it’s arguably better to sleep with someone who’s positive and has it under control, versus somebody who might have HIV but doesn’t know it yet. In that case, they will be in the acute phase of infection, when they’re most contagious.

It’s also possible for HIV-positive people to have uninfected children. Treatment in pregnancy can reduce the chances of a mother passing the virus to her child. That’s why HIV testing is often part of the standard first-trimester bloodwork.

There’s Still No Cure or Vaccine (But We’re Getting Closer)

For a hot minute, it looked like a baby had been cured of HIV. She was born prematurely to an HIV-positive mother, and doctors took the unusual step of treating the baby immediately after birth. She stopped taking the drugs as a toddler, and her viral load was undetectable for more than a year. This girl, the “Mississippi baby”, seemed to have been cured. That is, until the virus came back at age three.

When a patient’s viral load becomes undetectable, they still have the HIV virus in their body. It hides out in “reservoirs” like lymph nodes and bone marrow. One possible strategy for a cure is to “shock” the virus into coming out of hiding, and then kill it. AIDS researcher Paul Volberding, who is working on this approach, told CBS News:

We say our goal is to find a cure in five years and I think everyone understands that that’s more aspirational than actual. But I think it’s realistic to think that at the end of five years we will be a lot further along than we are now.

Vaccines have been in the works for a long time, and some people believe we’re getting very close. Researcher Louis Picker told Forbes that the vaccine he’s developing could be ready as soon as ten years from now. It only works after a person has been infected, and it tricks the immune system into killing the body’s own cells in the reservoirs where the virus is hiding. The vaccine is 50 per cent effective in monkeys.

“We would love if there was 100 per cent protection,” says Dr Kolber. “But think about it: if there was even 10-20 per cent protection, you would reduce transmission by that much and that’s a significant positive effect.”

With a vaccine, or a cure, HIV could become a thing of the past. But for now, our best bet is to take advantage of the tests and treatments we already have.

Michael A. Kolber, PhD., MD is a Professor of Medicine at the University of Miami’s Miller School of Medicine, where he is also the Vice Chair for Clinical Affairs, Director of the Comprehensive AIDS Program, and Director of Adult HIV Services.

Gerry Schochetman, PhD, is a Senior Director of Diagnostics Research at Abbott Laboratories.

Comments