Chances are you’ll wind up in outpatients at some point — even if it’s only for a minor injury. But the highly trained medical professionals who work in emergency medicine are prepared to attend to any urgent situation that arises.

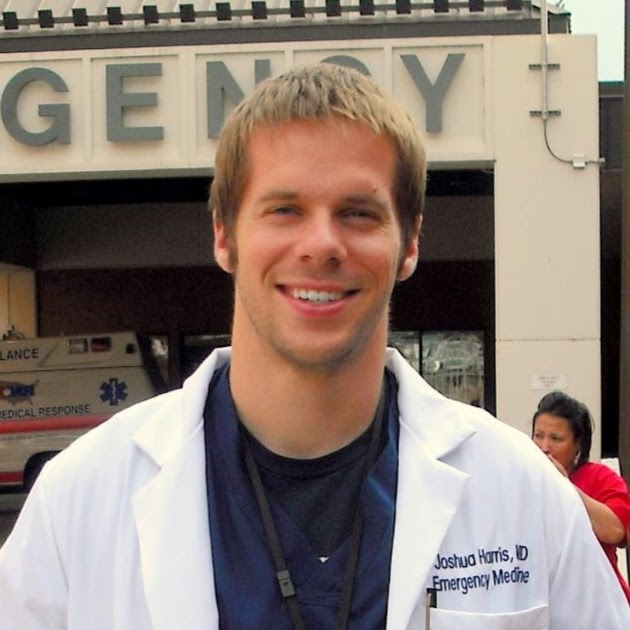

Photo by spotmatik (Shutterstock)

Joshua L Harris, M.D. is an emergency medicine physician in Vermont who is working hard every day to keep his patients comfortable and healthy, and takes special care to educate his patients about their likely diagnoses so that they can make informed decisions. We spoke with Joshua to learn how he came to his profession, what his day to day workload is like, and more.

What drove you to choose your career path?

A love of people and a love of science.

How did you go about getting your job? What kind of education and experience did you need?

Four years of undergraduate training, four years of medical school, and three years of residency in emergency medicine.

What sorts of things do you do beyond what the average person might expect? What do you actually spend the majority of your time doing?

I spend about 1/3 of my time in face-to-face patient encounters. The remaining 1/3 is reviewing past notes, labs, X-ray, CT and Ultrasound images, and making phone calls to other doctors, and the other 1/3 is documentation time.

When I’m calling other doctors, it’s the patient’s main doctor or a consulting specialist regarding their care. Regarding documentation, it takes a large amount of time to document the care I provide. I document what the patient tells me, their exam, my decision making process, their labs, X-rays, or results, and their discharge or admission information plus discharge instructions. For more complex cases, I may be documenting procedures, critical care (frequently in the room because someone is very sick), re-examinations, and so on.

What misconceptions do people often have about your job?

This is the main one: The ER is designed to provide emergency care to make sure you are safe, healthy, and comfortable. It is not an in-and-out clinic or a primary care office. If you come for something minor, you are likely going to wait. I’m 100% happy to take care of you, but the people who are very sick will always be cared for first.

What are your average work hours?

The industry average is 8-12 hours a day, 3-5 days per week. It varies significantly week to week. There is no such thing as a regular schedule in emergency medicine.

Are there any special techniques or habits you have for making it through a long day?

Other than being well-rested, well-fed, and well-exercised before coming into work, not particularly. It takes an enormous amount of physical and mental energy to make it through a full day. My shifts are only 9 hours though, which helps.

What do you do differently from your coworkers or peers in the same profession? What do they do instead?

All ER doctors try to provide a “standard of care”. Personally, I’m big on patient education and shared decision making between the physician and patient. I will often educate my patients on the situation, the data we have, what I think are the potential dangerous diagnoses and their likelihood, and if there are two or more potential courses of action. Then I ask my patients for their input. I will certainly provide recommendations to the extent that they are backed by research and accepted practice, but if the course of action is not clear, I educate my patients on what I know then as for their input.

What do you learn when specialising in emergency medicine that doctors in other fields might have less experience with? How would you describe your particular expertise?

I’m going to refer to the definition provided by one of our major governing bodies in the US, the American College of Emergency Physicians which defines us as follows:

“Emergency medicine is the medical specialty dedicated to the diagnosis and treatment of unforeseen illness or injury. It encompasses a unique body of knowledge …. The practice of emergency medicine includes the initial evaluation, diagnosis, treatment, and disposition of any patient requiring expeditious medical, surgical, or psychiatric care. Emergency medicine may be practiced in a hospital-based or freestanding emergency department (ED), in an urgent care clinic, in an emergency medical response vehicle or at a disaster site.”

Basically, we have to be ready to handle any emergency condition that occurs. This encompasses every body system. However, our knowledge base is focused on the emergent and immediate steps necessary to make sure a patient is safe, comfortable, and as healthy as possible. We are not focused on chronic or longitudinal care and we do not see patients on a chronic basis.

What’s the worst part of the job and how do you deal with it?

Patient satisfaction. I would like 100% of my patients to be happy with their care. Nationally, satisfaction of an ER visit is in the 80-85% range. Unfortunately, I feel that most of the time the unhappy 15-20% are unhappy about factors I can’t control. Wait times, workup times, and people who want chronic medical problems solved in the ER are top players. Trust me, this is equally frustrating for me too.

Do you have any advice for people who need to enlist your services — that is, your patients?

I think ERs need to come with a user manual! What I need to hear is a concise, descriptive explanation of why you are in the ER, without tangents. Telling me that you have abdominal pain and having no other description or history is not helpful. Stating that “it should be in my chart” is also not helpful as its not always the most up-to-date or accurate. Please also bring a list of your medications, allergies, health problems, and prior surgeries. Finally, everyone should know what their own and their loved ones’ final wishes are. Specifically, would you or your loved ones want CPR or a breathing tube? These are decisions that often need to be made in a seconds, and you should know the answer ahead of time. If you don’t know, ask your primary doctor for help deciding.

One more thing: the ER is always going to take care of the most sick patients first. This is frequently what accounts for how long you do (or do not) have to wait. If you have something that might not be an emergency, please call your primary care provider first and see if it is something they can help you deal with. You are likely to get more prompt care and they can help you follow up on the issue, whereas we cannot. The silver lining: if you are waiting, you are not dying. Feel sorry for the people who get rushed back.

How do you move up in your field?

The only “move up” is into administration or medical politics. There are few other advances.

Entertain my ignorance: specialising in emergency medicine means that you’ll always be working in that field, correct?

Correct. To become another type of physician, I’d have to do another residency. It is done occasionally, but is the exception rather than the rule. So once you are an ER doctor, you are always an ER doctor without significant effort via another few years of training. I’d have to stop being an attending physician while I did another residency which entails a significant pay cut and going back to an 80-hour work week.

What advice would you give to those aspiring to join your profession?

Be absolutely certain that you want to do it. It takes 7-15 years after undergraduate school to get into practice, with most new physicians already being in their thirties, and as above, with a significant amount of private debt. With that said, it’s a very rewarding career and if you love it, do it

Career Spotlight is an interview series on Lifehacker that focuses on regular people and the jobs you might not hear much about — from doctors to plumbers to aerospace engineers and everything in between.

Comments