It’s awkward enough talking about death with other adults. It’s even harder when you have to explain to impressionable children that a loved one is gone forever. Here are a few tips for approaching this difficult but inevitable topic in the best way possible.

Base Your Discussion on the Child and Situation

First off, there’s no one-size-fits-all way to talk to children about death. Every child is different, and you have to take into consideration how old, sensitive, and mature the child is, not to mention his or her relationship with the deceased. A five-year-old might be fine with a simple explanation that so-and-so is gone, while a 10-year-old or teenager would understand the permanence of that and feel it much more acutely. You know your kid best and should use that understanding to help guide what you say.

For example, behavioural therapist Janet Lehman, says to look at your child’s temperament:

If your young child is introverted, observational and reflective, let them know of the death in simple and clear terms. Don’t expect that they will want to or be willing to share their feelings. Instead offer other ways for them to express their feelings via a art project- a card or picture to remember the loved one, writing a poem or song (older introspective child), or even something like planting a tree in memory of the loved one.

For a more extroverted child, set aside ample time to discuss the questions, comments, and concerns about the loss. These kids may respond to other forms of expression like running a race in memory of the person, volunteering for a related cause to honour their memory, etc.

It’s usually best to let the child lead, most of the child psychology experts I talked to said, while you support them in a way that’s appropriate for their age and development. David R. Castro-Blanco, an associate professor in the department of clinical psychology at the Adler School of Professional Psychology says:

The “rule of thumb” regarding discussing death with children, is to talk about it in a way that matches the child’s developmental level. In other words, don’t give the child more than s/he can handle, in the name of being “honest” or “accurate”.

As a parent, discussing one’s own mortality, it’s probably better, especially with younger children, to reassure them you won’t leave or “abandon” them, than to be statistically accurate and predict the odds are low. Children deal in absolutes, and hold tightly to their parents as an anchor to stability. They need to believe in the availability and consistency of that anchor.

Another example of basing your discussion on the situation: At a very young age, my daughter talked a lot about death — mostly saying things like she never wants to lose me and wondering what would happen to her if she died. As disturbing as those discussions have been, I’ve realised that it’s more her natural curiosity (and maybe natural disposition to existentialism) than serious grief behind those questions, and so have been trying to talk about them in a reassuring, matter of fact manner (instead of my natural instinct of screaming “What are you talking about! You’re just a toddler, don’t think about death!”).

Listen and Ask Questions More Than You Talk

As is usually the case whenever you’re talking with someone about a sensitive situation, it’s better to truly listen and ask questions, rather than assume what the other person is thinking. This is especially true when we’re talking to children about something as fearful and somewhat abstract as death. Family and marriage therapist Erica Curtis advises:

Sometimes because of our own anxiety discussing the topic we miss the mark by sharing too much, too little, or the wrong stuff. Before you start sharing information or answering questions, get a sense of what the child believes and, for that matter, what the child is actually asking. “What do *you *think happens what someone dies?” “What would *you *like to happen?” Questions like these will give you a better sense of your child’s inner world, their thoughts, and what they are trying to figure out.

When one child asks “but what happen to grandma?” she may be wondering what happen before she dies, whereas another might be wondering what happened after. These are very different questions. You can simply ask some clarifying questions: “what happened to grandma before or after she died?” Likewise, when an adult hears the question “where did she go?” we often think about answers such as “heaven” or “she was buried.” However, a child may be remembering her going to hospital.

How much or little to share and explain is probably the biggest question, but, again, let your child lead the way. Child psychologist Dr Susan Lipkins says that one rule of thumb with talking to children about death is to only answer the question that the child asks — don’t give long, complex explanations, but instead answer the child’s questions at the level he or she is at.

Be Honest, But Avoid Potentially Traumatising Information

It might be tempting to gloss over a death or give a different reason for it (particularly if it wasn’t a natural death), but Dr Jenny Yip, a clinical psychologist who works specifically with children and specialises in anxiety and OCD, recommends using as much honesty as possible (a good practice whenever you’re talking with your children):

If it was a natural death, parents can explain that death is a part of life, all a part of a natural process, that allows the world to survive. When speaking of someone who was very close to the child, it is very important to be clear and honest. Dishonesty can hurt the child more and often causes confusion for many years ahead, especially is she hears a different story from other relatives or friends.

That is, again, depending on how ready the child is for this information.

It’s fine to share how you’re feeling, but since kids will often imitate their parents, be mindful of your reaction around them. Coping with grief, unfortunately, is a lesson kids have to learn — and do learn from the adults around them.

Some approaches are better than others, so be careful what you say as well. Dr Kristine Kevorkian, who has a doctoral degree in thatanology (the study of death and dying) and counsels terminally ill patients and their families, writes:

Please do NOT say that “Grandma Joan went to sleep and she’s in heaven now.” A child might be so afraid that he/she might never go to sleep again. If a loved one has been ill, explain what that means to the child, not that Grandma Joan was sick and is now going to sleep forever.” Or, “Grandma Joan has cancer and is going to heaven.” What is cancer? Does everyone die from cancer? Give details and throughout the conversation, ask the child to repeat what’s been said in order for the adult to hear if the child is actually listening and hearing what’s being said.

Provide Outlets for Grieving

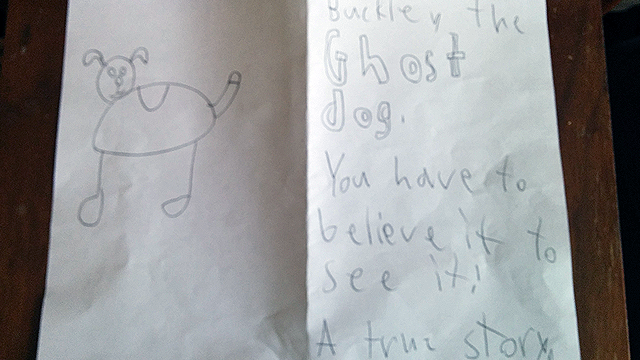

A year ago, my husband and I had to put down our beloved dog, whom my daughter had known for all of her seven years of life. Since then she’s been talking about him as if he’s a ghost she can see, pet, and talk to. She writes stories about him, saying he comforts her at school and other times.

As heart-wrenching as this has been for us, the experts I talked to assure me it’s healthy grieving.

Arts and crafts, writing, photography and any other activity children enjoy can help them honour and remember the loved one who’s died — and also teach them that even if someone has gone, they’re still alive in our minds and hearts.

Watch Out for Unusual Behaviour

While there are no hard and fast rules about how anyone grieves, after an extended period of time with very troubling symptoms, you might want to consult a professional. Dr Hani Talebi, a psychologist in Austin, Texas, points out these issues that could suggest a child (or anyone else, for that matter) is struggling very much after a death:

1) Sleep problems (difficulty with sleep onset or maintenance);

2) Externalizing behaviours (aggression toward peers, oppositional/defiant, emotional dysregulation, etc.);

3) An inability to have fun engaging in activities which they previously enjoyed;

4) Withdrawal (tearfulness, an unwillingness to communicate their thoughts/feelings, isolation, etc.);

5) Developmental regression (i.e. acting childish or much younger than their actual age).

Otherwise, if the kid seems generally him/herself, don’t worry. Just listen. Be there and be well, and you’ll both get through it together.

Comments

One response to “How To Talk To Your Kids About Death”

or perhaps any of the proposed criteria for prolonged grief disorder in the dsm 5 (

http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/729406_2) and or symptoms of depression/anxiety (which some say are basically a reaction of sorts to actually losing something/someone and the fear of losing something/someone).

String theory invalidates religion and evolution because all life is the same life at superposition. The. Human race doesnt know shit about reality.

And all numbers are the same number because they become indeterminate when divided by zero… Mods, why you no ban troll?