As a disciplinary strategy, spanking is definitely out: It not only doesn’t work, but it’s associated with the same negative outcomes, to a lesser degree, as those that result from child abuse.

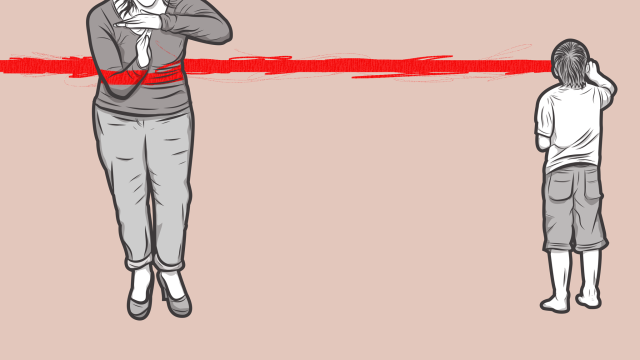

Sam Woolley/GMG

Which leaves us with the time-out as the major tool in the discipline toolbox. The trouble is, a lot of parents don’t think that time-outs work — either they can’t get their kid to stay in time-out, or it doesn’t actually make the kid behave any better.

“Whenever I hear, ‘I can’t do anything to stop her,’ I cringe,” Mike Fraser, a child psychologist in New York City, told me. “They have taken away all authority from themselves. They have resigned themselves to the fact that their six-year-old is going to run the house.”

The problem, Fraser says, is that most parents aren’t doing time-outs correctly. I spoke to him for some advice.

Ask ‘What Kind of Family Do We Want to Be?’

This is an important first step in creating the “culture” of your household. If you need some guidance on this, Fraser suggests this framing: In our family, we are safe, responsible and respectful. These three words cover a lot of ground for the behaviour you want to support. For example, you want your kids to speak to you and each other respectfully; you don’t want them to, say, swing their baseball bats in the house; you want them to control themselves with screen time when given some leeway. Over time, emphasising these three policies will help your kids regulate their own behaviour, because when they don’t, there’s a negative consequence. (It also requires, of course, that you and other adults in their life are also modelling safe, respectful and responsible behaviour.)

Be Consistent

Consistency is the key to permanently changing behaviour, even for adults. Fraser asks, “You know how when you park your car in a city, you pay close attention to the parking regulations — the time on the meter, the alternate-side parking rules? That’s because parking meter attendants are extremely consistent. You don’t gamble and think they’re not going to be there. They’re always there.” This has, broadly speaking, changed our behaviour: We don’t want a ticket. We (mostly) follow the rules.

The same goes for kids — we need to enforce the consequences like a robot if we want to see any effect.

[referenced url=”https://www.lifehacker.com.au/2017/09/reduce-day-care-drop-off-tears-with-a-goodbye-ritual/” thumb=”https://i.kinja-img.com/gawker-media/image/upload/t_ku-large/x0s9ktddjf2bvk1ttie6.jpg” title=”Reduce Day Care Drop-Off Tears With A Goodbye Ritual ” excerpt=”Dropping off a young child at day care or preschool can be rough. There may be protests and wailing. Your kid may latch onto your leg for dear life. When my daughter started going to day care when she was one and a half, she cried every day for the first six weeks. The teachers were great, and I knew she was safe and cared for, but I ached seeing her so sad.”]

Memorise These Three Words: Expectations, Rules and Consequences

Time-outs, and shaping children’s behaviour more generally, depend on their knowing the rules and expectations of the household. “Successful time-outs aren’t just an ‘in the moment’ thing,” says Fraser. “It’s a whole process. It’s like a workplace: People know what the expectations are. There are rules and consequences.” If your rule is that homework must be finished before screen time, make that clear. If your expectation is that children should help clear the table without being asked, that should be clear too. The consequences, both positive and negative, are directly tied to the behaviour: If you cheerfully help with the grocery shopping, maybe you get to pick out a treat. If you whine the entire time we’re in the store, you lose a privilege.

A time-out is a natural consequence for some negative behaviour: Hitting, screaming in the lolly aisle, refusing to put on shoes, and so on. Fraser outlines a four-step process for an effective time-out that will eventually shape appropriate, social behaviour:

1. Look Them in the Eye

“Get down on their level and make eye contact,” says Fraser. “Explain what they’re doing wrong, and get back to the words unsafe, irresponsible or disrespectful.” For example, “You are responsible for putting on your shoes so we can get to school on time. When you don’t put on your shoes, we are late.”

2. Give Them a Chance to Make Good by the Time You Count to Three

Tell them what rule they have broken, and give them a chance to remedy the situation: “Can you put on your shoes by the time I count to three?” and then start counting. “Don’t do two and a half, two and three-quarters — if you’re going to count to five, count to five,” says Fraser. If they can’t put on their shoes, or apologise to their brother, or stop screaming in the checkout aisle, the time-out begins in their room, or on the time-out step, or wherever.

The language is important here: You are not “putting them” in time-out — they have earned a time-out as a consequence of their actions.

3. Start the Timer

Set them in their time-out place — either a “naughty” chair or step or a specific place in their room — and start the timer for one minute for every year of age (so three minutes for a three-year-old, four for a four-year-old, and so on). If your kid won’t stay in time out, you have to return them — neutrally, without getting angry — to the time-out spot. This is where patience comes in. “Even for parents who are willing to put in the work, [this is where] they tap out early. They fold under pressure,” says Fraser. Take a look at this video of Supernanny, in which a defiant three-year-old is placed back into time-out 67 freaking times.

Fraser says, “They will test the parent by getting up and running away from the time-out seat. You can’t give up. Eventually they will give up. If you can’t physically manage it, get a family member to help.”

Fraser does note that there are some children for whom time-outs really don’t work — he cites children with developmental delays, and agrees with me when I ask about children with mental illnesses. “If this is something you’re really struggling with, you might want to consult a medical professional,” he says. He also notes that in extreme cases, if a child is completely out of control — for example, destroying things, punching holes in walls, tearing up the house — and you’re afraid for their safety or your own, “You have to be prepared to call [000].”

4. Insist They Apologise

When the timer dings, “they have to appropriately apologise. This is the moment to learn what a ‘good’ apology is — they have to say it so the person receiving the apology really feels [that they’re sincere],” Fraser says.

None of this is easy: “You have put in the work, and it’s really hard,” says Fraser. It’s tempting to give up, to think that eventually they will “grow out of” their bad behaviour. But Fraser notes that we immediately correct other mistakes our kids make — we would never think of letting the statement 2+2=5 stand, for example, “because we know that to not understand maths is a severe disadvantage. It’s the same with behaviour — this is ultimately a process of teaching a child how to be in the world.”

Comments