It’s easier than ever for someone to create a website and post completely made up stories that become international headlines. This makes it harder to tell truth from fiction or share news with others who may not be able to tell the difference either. Luckily, fake news isn’t too difficult to spot. Here’s how, and how to filter it out of your feeds.

Fake News Sites Make Up Completely Wrong Info

A collection of headlines from a site that openly makes up stories.

Whether or not you think fake news determined the outcome of the 2016 US presidential election, it certainly had an influence on it. This year we saw a growing number of sites designed to get attention with completely made-up stories. At best, these sites misinform people who read them, and at worst they drown out legitimate news in a ceaseless flood of stories that need to be debunked. Often these sites will bill themselves as “satire” or claim they are “for entertainment purposes,” though they may omit the disclaimer entirely. Writers for these sites don’t aim for anything even resembling authenticity.

A man named Paul Horner created several such sites. He owns several real-sounding URLs including nbc.com.co, and abcnews.com.co. Note the extraneous “.co” at the end of those sites. None of these are associated in any way with the news organisations they’re named after, but if you don’t look too closely at the link you click on, they appear legitimate. These sites offer entirely made up stories that could sound real if you’re not very well informed, or looking for something to subsidise your world view.

One of Horner’s sites claims that US President Obama will run for a third presidential term. This is illegal l under the 22nd Amendment. Another claims that Obama signed an executive order to investigate the results of the 2016 US election and to schedule a “revote” for December 19th. This is also illegal, and impossible. Even though these stories are obviously fake, the idea that they could be true gets people riled up. They get passed around anyway, used as ammo for arguments and viral bait for people looking for something to support their confirmation biases. As a result, those sites get huge advertiser revenue.

Horner himself said in an interview with The Washington Post, this happens because his readers don’t fact check stories. The New York Times similarly interviewed fake news site owner Beqa Latsabidze, who said that generating fake stories “is all about income, nothing more.” While both Horner and Latsabidze claim their sites operate as “satire,” it’s an open secret that if no one fell for the ruse, their sites would have a harder time making money. To make matters worse, Facebook has a vested interest in showing readers stories they like, even if they’re not true. As Gizmodo reported, Facebook has the tools to shut down fake news sites, but have failed to use them because they were afraid it would make them appear biased. Instead, your friends or even Facebook’s trending news module could potentially bring you completely false news stories and Facebook will reward it exactly as if it were true.

Completely fake news sites are everywhere, but they’re also among the easiest to avoid. Extensions like B.S. Detector will let you know when you’re about to click on a link from a questionable source. You can also check a site’s URL. Most major news sites will redirect to a .com or .net domain, even if they own other versions of a URL. If you’re reading a site that ends in less common domains like .co, search online for the name of the news outlet to find their real site first. If you can’t find the article you’re reading on a more reliable domain, don’t trust it. Finally, look at a site’s footer. Many sites will have a disclaimer stating the site is “satire” or provide another giveaway that it’s less than legitimate.

False Stories Can Proliferate On Legit News Sites Without Careful Scrutiny

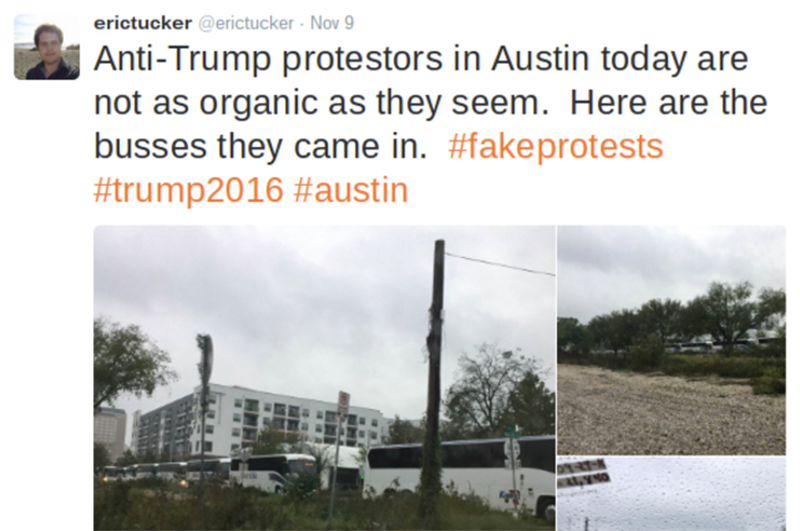

This tweet claimed buses were used to bring in protesters. They were not. Some sites still reported it.

It’s relatively simple to spot news that comes from made-up sources. However, some false stories can still pop up through legitimate news outlets. In some cases, those sites jump on the potential news without adequate research or confirmation, and the result is a false story that goes viral. Even if a later post debunks it, it usually falls short of the original’s popularity. This is “fake news” in that the story is fake, even though the outlet publishing the story is real.

The New York Times provides an in-depth example of how fake stories can spread in this piece. In this example, Twitter user Eric Tucker photographed several buses near a post-election protest, claiming that the protests were “not organic,” including the hashtag “#fakeprotests.” The story was picked up by multiple small news outlets. However, the claim was false.

Further investigation found that the buses were hired by a company called Tableau Software for a conference. The buses never transported protesters and had nothing to do with politics in any way. However, the story was shared thousands of times on social media, and by that time the damage was already done. While it wasn’t covered by major news outlets, it did make the rounds on smaller news sites like Right Wing News and The Gateway Pundit — particularly those that appeal to the edges of the political spectrum — as well as being shared by public figures including Joe the Plumber. The tweet that kicked off the story was errant and improperly informed, but it still created a story with no basis in reality.

In a similar situation, a few tweets from a single Twitter user kicked off a firestorm of reports that CNN accidentally aired 30 minutes of porn. As Gizmodo reported, this is very unlikely to be true. No one except this one Twitter user saw the alleged porn, and CNN claimed it could find no evidence that its Boston-area broadcast was interrupted. Despite flimsy evidence — that could very well have been a hoax or an isolated error — the story was picked up by The International Business Times, Independent, Mashable, and more sites. Many of them used a headline that positioned the story as a question. “Did CNN Really Air Porn For 30 Minutes?” When stories have to use questions as headlines, the answer is usually no. It’s also a sneaky way to run a story without confirming it.

These types of stories are harder to combat because in some cases, the truth is harder to ascertain, and it never has the same viral reach as the lie. In this case, fact-checking sites like Snopes, Politifact, and FactCheck.org can be helpful. In the case of the buses, Snopes posted this article explaining the mistake. The downside is these sites aren’t always fast enough to keep up with false stories. Snopes’ dress down of the bus story was posted on November 11th, two days after the original tweet and a day after articles about it appeared online.

It’s also important to remember that no fact-checking site is perfect. While they’re helpful for debunking obvious hoaxes or blatantly false information, they’re not designed to be thorough. If you find a claim that’s dubious in an article, check out the story (where available) on fact check sites, but be sure to augment your reading with more analysis from both inside and outside your bubble.

Accusation-Based Reporting Gives a Misleading Impression of Real Stories

This version of a CBS article echos an accusation without evidence. It was later changed to reflect an accurate version of the story.

On top of people making stuff up online (whether intentionally or accidentally,) political and corporate figures often muddy the news waters with accusations. In an attempt to promote “neutrality,” many news outlets are hesitant to claim a statement made by a public figure is outright false, even if it’s demonstrably so. Professor of Journalism at New York University Jay Rosen calls this accusation-based reporting.

Accusation-based reporting follows a basic structure:

- Person A makes an accusation against Person B.

- Person B denies the accusation.

- A news outlet reports that the accusation has been made and denied, but doesn’t offer any information to support or disprove the accusation.

- The accusation itself, not the accuracy of the claim, is treated as the newsworthy story.

Rosen says this runs counter to evidence-based reporting. In evidence-based reporting, a story should lead with information about the veracity of the accusation. If there is no evidence to support the accusation, a story should say so. If there is evidence to disprove an accusation, the piece should say that as well. The evidence should be given top billing, instead of the accusation.

For example, when President-Elect Donald Trump claimed that millions of votes were cast illegally, costing him the popular vote. As Rosen points out, accusation-based reporting would present this accusation as valid until disproven merely because it was stated by the president-elect. In an evidence-based report, there must be evidence before a story is treated as true. In this particular case, The Washington Post explained that there has been no hard evidence of mass voter fraud on the scale the president-elect mentioned. Recount efforts are underway in several states, but until the recounts are finished or data is released, there’s no evidence to rely on, only accusations.

While most news outlets at least reported this information, many legitimate organisations feature headlines that simply quote the president-elect’s assertion, giving the impression that the accusation is more credible than it is. This practice presents the claim in a bombastic way to draw in readers, but it sets a misleading tone from the outset.

This is particularly a problem when readers are flooded with stories they need to fact-check. It puts the burden on the reader to verify every claim (including the ones in the very headline they just read), instead of getting accurate information as easily as possible. In the race for sensationalist clicks, casual or busy readers can become misinformed. Worse yet, accusation-based stories without evidence can serve as powerful distractions from legitimate stories where there is evidence to examine.

Unfortunately, this particular brand of fake news is one of the most common and even large outlets are guilty of it. To avoid falling victim to accusation-based reporting, consider how a story is structured and what kind of proof it offers. If a story merely repeats the accusations and defence of the people involved, there’s probably a better version of the story out there somewhere else. Once again, fact-checkers and in-depth reporting can be helpful in this area.

When misinformation runs rampant, it’s easy to claim that there’s no good journalism left in the world. In reality, there is, it’s just drowning. For every lengthy story that dives into the details of a complex and nuanced topic, there are a hundred stories that parrot a false claim or just make stuff up. Meanwhile, social media and the tools we use to consume news let us pick and choose the stories we like best. The result is that we can become overwhelmed with fake stories and lose our ability to determine what’s real. We’re smart enough to tell when something’s fake news, we just don’t have the time to validate every story. Eventually, stuff slips through the cracks and we’re left with the impression that we get from unvetted claims.

Unfortunately, there’s no one simple solution, but we can start by not sharing stories simply because they make us mad. Fake news and misleading stories thrive in anger. News rightly gets an emotional rise out of us when a story is true, but when it’s false, that emotion can give a lot of power to baseless accusations which make us less informed and more polarised. Neither of which helps improve the news we read.

Comments

One response to “How To Spot And Debunk Fake News”

Fake news, you mean like CNN and all the other “mainstream” media outlets telling everyone that their polls show Trump had no chance of winning.